Red River County

Charting Routes and Connections

Sold into Slavery: Eli Terry’s Journey from Freedom to Slavery and Back, 1842-1850

In 1840, two men kidnapped and sold Solomon Northup, a free Black man, into slavery. The movie Twelve Years a Slave (2013), popularized Northup’s story. While the movie dramatized his experience, most people don’t realize that countless other free people of color were captured and sold south into slavery. Although many never experienced freedom again, a few, like Northup, managed to escape.

This is one such story.

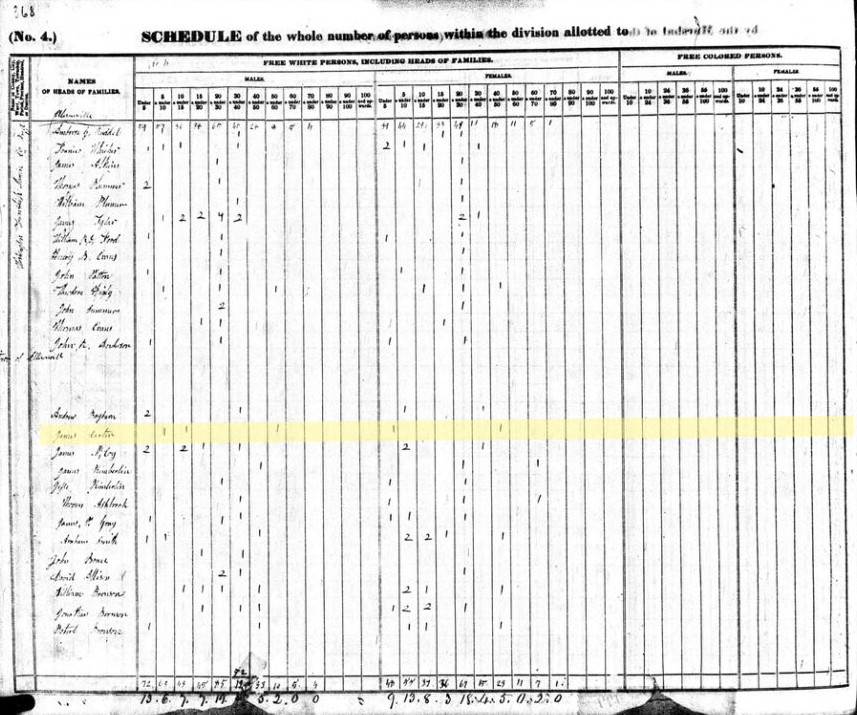

Eli Terry was born sometime around 1818. Although it is unknown where he was born or what his status was at birth, in 1840 his father, David Terry, a free man of color, appears on the federal census for Marion County, Indiana. Terry’s household included two young men between ten and twenty-four, one man between twenty-four and thirty-six, one man between fifty-five and 100, two girls between ten and twenty-four, and one woman between thirty-six and fifty-five.

In 1840, Eli Terry would have been around the age of twenty-two and it is most probable one of the two young men that appears here in David Terry’s household.

Although it is not clear when David Terry moved to Indiana (he does not appear in the 1830 census) he likely migrated there like many other Americans, hoping to claim land and create better opportunities for himself and his family. Early settlers could purchase sections of land in 640, 320, 160, 80, or 40-acre plats for approximately $2 an acre.

The Northwest Ordinance (1787) technically prohibited slavery in the new territories (some settlers in southern Indiana brought people they enslaved with them). Settlers who brought enslaved people with them prior to 1816 (the year Indiana became a state) were allowed to keep them.

As a free Black man, however, opportunities were limited even in a “free” state.1 Free Black men could not vote in Indiana or serve in the militia. And, like in most states, they could not testify in court against white people.

The Indiana legislature further diminished those rights in 1831 when they passed a law requiring all Black residents and newcomers to register with local authorities and pay a $500 bond attesting to their “good behavior.” Presumably, they would forfeit that bond if they violated (or were thought to have violated) community standards.2

In 1851, a change to the Indiana constitution prohibited Black and mixed-race people from coming into or settling in Indiana at all.3 Those who lived there prior to the new law, however, were allowed to stay.

As a young man in Marion County, Eli Terry would have worked alongside his father on their farm growing subsistence crops, raising livestock, and perhaps growing corn and wheat to sell in the expanding local marketplace.

Eli Terry’s life was upended in 1842.

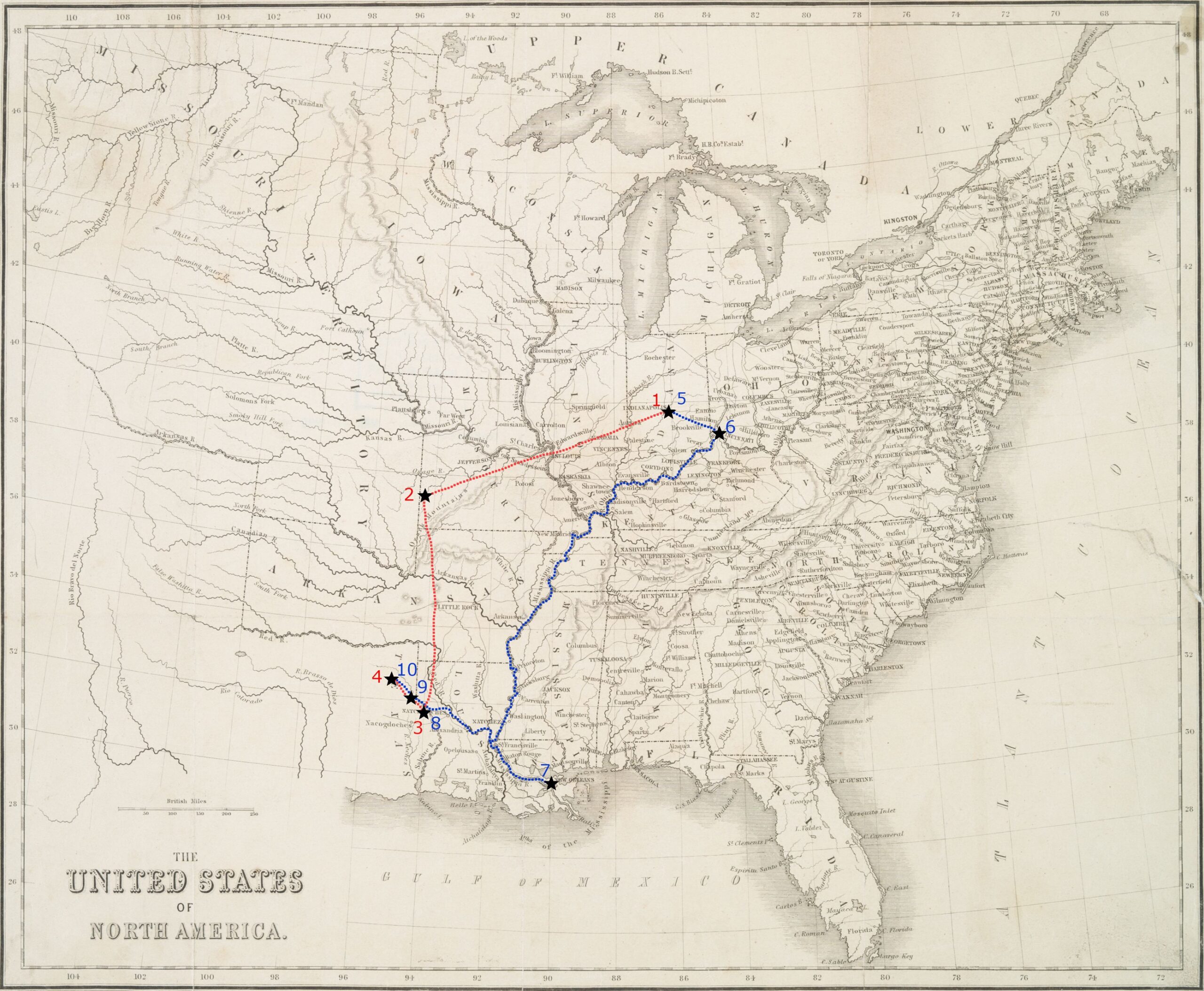

In the fall of 1842, James Carter hired Terry to drive a team from Indianapolis to Jasper County, Missouri. The approximately 500-mile journey would have taken almost three weeks.

Terry was enticed by Carter’s offer of “good wages for one year” and his promise that at the end of the year they would return to Indiana.

At the end of the agreed upon year, Carter paid Terry “by letting him have a horse, saddle, and bridle.”4

Although nothing is known about Carter and how he came to know Eli Terry, and Terry left no record of his experiences, two of the men involved in his story did.

The two extant records documenting what happened next offer differing accounts as to how James Carter explained the beginning of their “return” trip back to Indiana.

THE SWINDLE

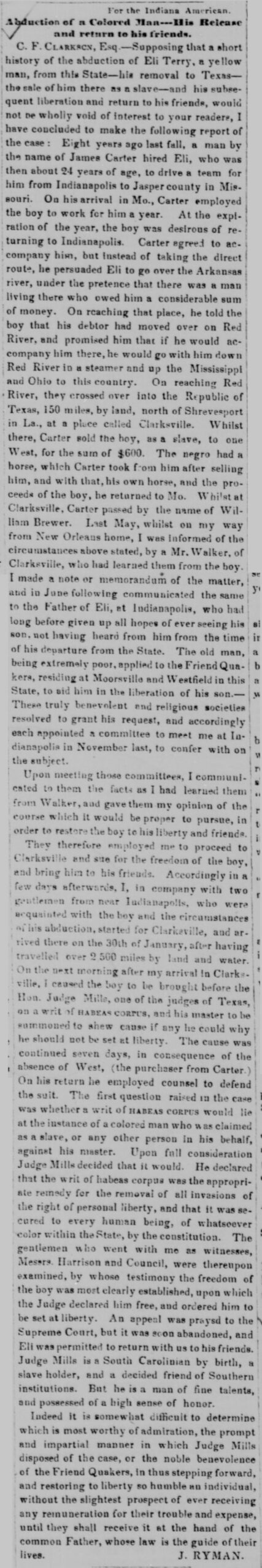

According to an article that appeared in the Indiana American on February 15, 1850, James Carter told Eli Terry that he needed to cross the Arkansas River to collect a sizable debt owed to him. Once they arrived at their intended location, Carter changed his story and said that they needed to cross the Red River to find the man who owed him money. Carter then promised Terry that if Terry would travel with him, once the errand was complete, they would travel by steamboat down the Red River and up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to return home. This must have been an attractive offer since traveling by steamboat was much easier and quicker than traveling overland. In the fall of 1843, they crossed into the Republic of Texas north of Shreveport, Louisiana and then traveled 150 miles to Clarksville.

There are similarities between the account in the newspaper and the account Thomas W. Council published after Terry’s safe return to Indiana. According to Council, James Carter, his son, and Eli Terry set out from Missouri together. They traveled for several days before Terry expressed concern to Carter that they were not headed in the right direction. Carter acknowledged that they were not heading to Indiana, but rather were going to the Arkansas River to see Carter’s brother. Once there, “they would sell their horses, and then go by water, as it was much the easiest way of travelling [sic].”5

When they arrived at their destination on the Arkansas River, Carter claimed that his brother had moved to Red River County in Texas. Traversing through the Choctaw nation, they arrived at the Texas border. Carter, as the story was told to Council, “told the negro that it was contrary to the laws of Texas for a free colored man to remain there, as he was subject to being taken up and sold, consequently, the negro must acknowledge Carter as his master.”6 If this version is to be believed, Terry might have done so. Although it is not clear who he would have made this declaration to, if he made it, it did not legally change his status.

The trio stopped two miles outside Clarksville, the county seat of Red River County, and set up camp. Carter and his son left Terry in their encampment and went into town.

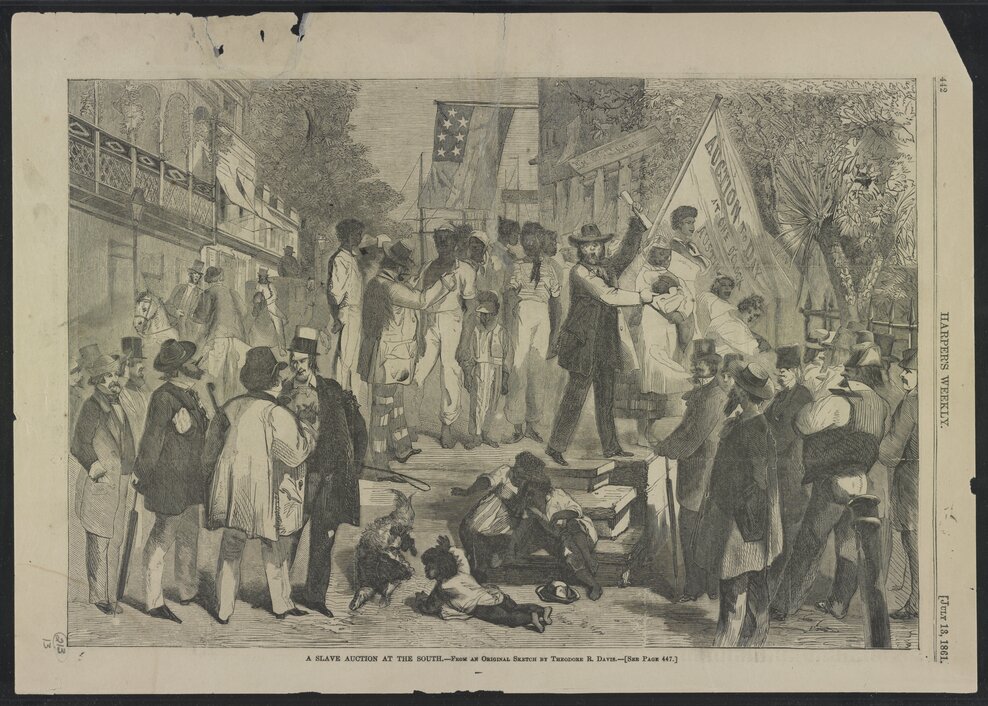

THE SALE

Once in Clarksville, Carter changed his name to William Brewer and sold Eli Terry to Major Edward West for $600.7

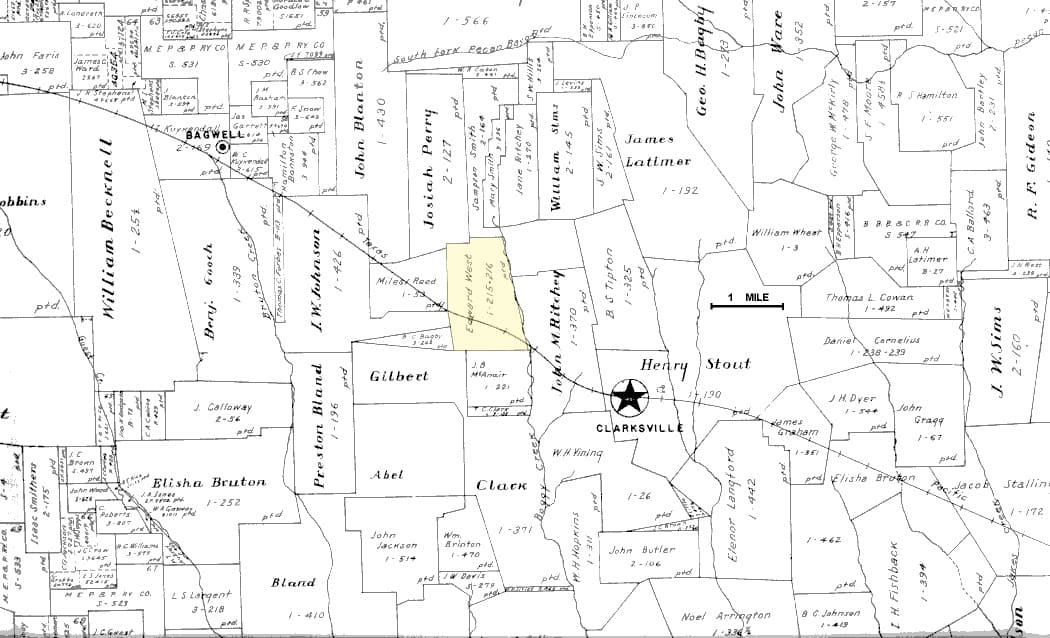

Major West was a member of a prominent land-owning family who settled in Red River County in 1833.8 They had deep roots in the community and West was widely respected. He served as the first appointed sheriff in Red River County after Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836.

The Wests, as shown on this land grant map, lived approximately two and a half miles northwest of Clarksville.

Carter accepted $300 in cash and a promissory note for the remainder. He then “traded [the promissory note] to a man by the name of Reed, for a tract of land; the land was then sold for cash.”9

After Carter struck the deal with West, he and his son returned to their camp, took the horses, including the one he had given Terry as payment for his work, and left. The next day, West showed up and claimed Eli Terry as his property.

Eli Terry repeatedly told West that he was a free man. West ignored Terry’s assertions. He must have believed him though because when Reed attempted to collect on the promissory note that he now held for $300, West refused to pay, alleging that he had been defrauded.10 Despite the fact that West likely believed Terry’s claim, according to Council’s account, he threw “every obstacle in his way that he possibly could, to prevent his obtaining his freedom.”11

West changed Eli Terry’s name to Jack and enslaved him for seven years. It was not uncommon for enslavers to change the names of the people they purchased. For Eli Terry, this was just one step in the erasure of his life as a free man.

Eli Terry’s assertions that he was free fell on deaf ears. That did not stop him from attempting to free himself. Like countless other enslaved people, he “made several attempts to run away.”12 If Terry persisted in asserting that he was really a free man and attempting to free himself, he was likely severely punished, like Solomon Northup for insubordination and challenging West’s authority.

As an enslaved person in Red River County, Eli Terry would have been forced to work in the fields. Farmers and planters in Red River County grew corn, oats, wheat, and cotton and raised livestock. Like Mose Hursey, Eli Terry would have planted crops, raised livestock, and performed odd jobs on West’s land. Perhaps he also attended Sunday prayer meetings and relied on religion as a means of survival. Religion played an important role in many enslaved peoples’ lives and provided them with a means to simultaneously pray for salvation and retribution.

THE RESCUE

The mission to rescue Eli Terry began with a fortuitous encounter in May 1849 between an attorney from Lawrenceburgh, Indiana, and a man from Clarksville, Texas. John Ryman was on his way home from New Orleans when he “was informed of the circumstances above stated, by a Mr. Walker, of Clarksville, who had learned them from the boy [Eli Terry].”13 How Walker came to know of Eli Terry’s situation remains unclear. But the next month, Ryman contacted Eli Terry’s father in Indianapolis. Terry’s father “had long before given up all hopes of ever seeing his son, not having heard from him from the time of his departure from the State.”14

Eli Terry’s father began searching for a way to bring his son home. Unable to afford the rescue on his own, he contacted the Friend Quakers in Mooresville and Westfield, Indiana, and pleaded for their assistance.

Quakers, also known as the Society of Friends, were known for their strong anti-slavery stance. They agreed to help. They hired Ryman to travel to Clarksville, Texas and sue for Eli Terry’s freedom. Two men who personally knew Eli Terry and could testify to his status as a free man accompanied Ryman on his mission.

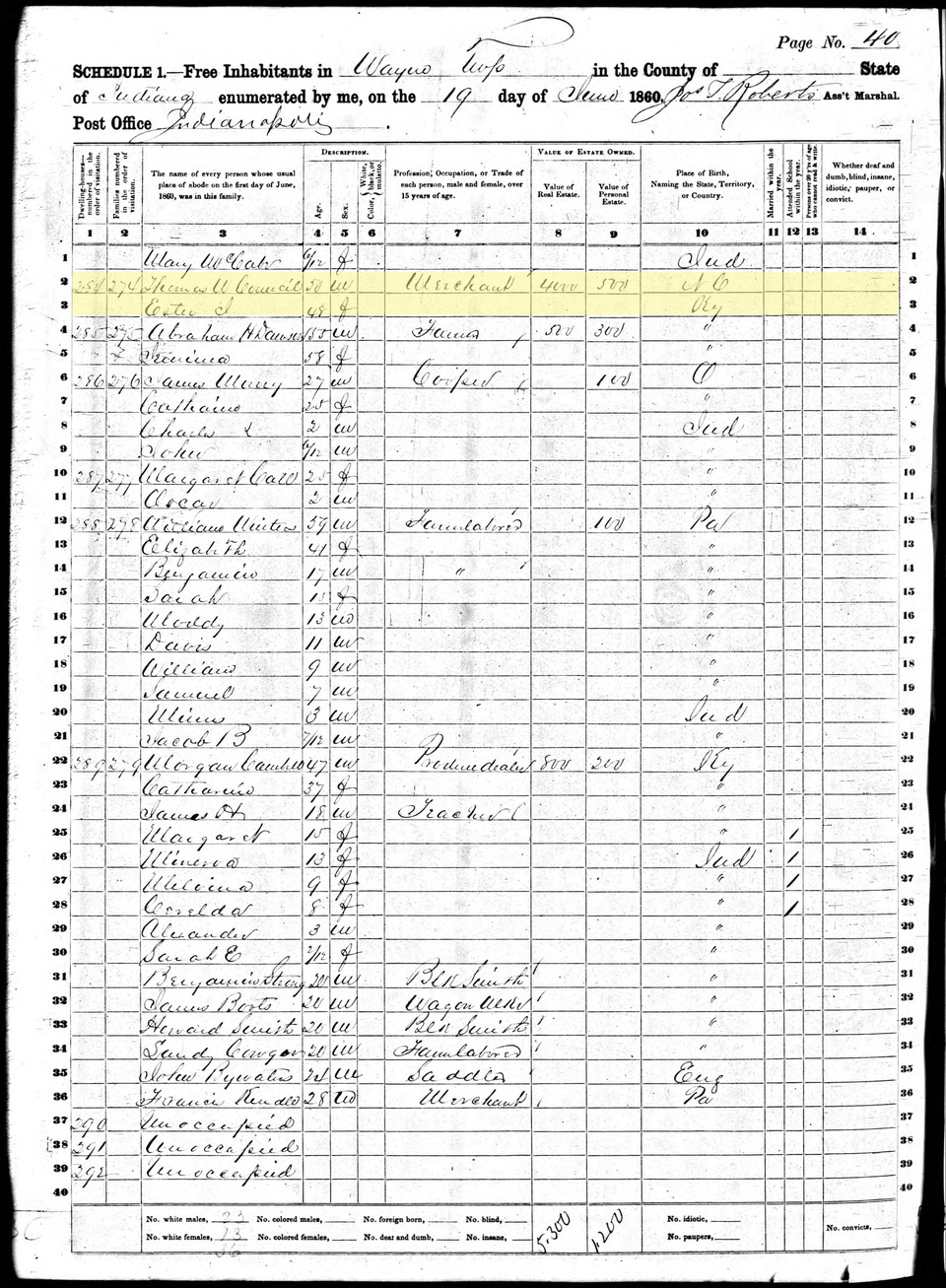

On December 9, 1849, Thomas W. Council and Mr. Harrison (first name unknown) boarded a train in Indianapolis and began the 2,500-mile journey south. Council, a merchant from Marion County, presumably conducted business with the Terry family. He and Harrison could identify him as a free man.

Once in Cincinnati, they arranged for passage to New Orleans. Situated on the northern bank of the Ohio River, Cincinnati served as a major market where sugar and molasses arrived from the south and pork, flour, and other commodities from the west. Cincinnati also had a long history of abolitionism.

As Council recorded the details of their travel in his journal, he noted the “dilapidation and decay” of the towns along the river and described the agricultural shifts evident along the Mississippi—from corn to cotton to sugar.15

“On entering the first of these, the traveller [sic] may regard himself as entering not only a region of corn, but the latitude of slavery, where the philanthrophist [sic] and statesman may commence the study of this institution to good advantage. Its withering, blasting, and unholy influence, seemed to rest upon every thing; which unavoidably raises in the bosom of every man not connected with it, a longing desire, if there is a spot upon the face of the broad earth not under its influence, to make such spot his home; and he would seek such a sacred place as the shadow of a rock in a burning desert. Here we saw the overseer, with his long bull-hide, as it is called, wound several times round his shoulder, passing under the opposite arm, making a coil similar to the rattle-snake when he prepares to strike his deadly fangs unto some unsuspecting victim, but more potent in its character, and more to be dreaded by the defenceless [sic] slave who suffers under its tortures, by which is filched out of their flesh and blood the wealth the master squanders upon the gratification of every animal passion, which prepares him for no higher place in the scale of human existance [sic], than the execration and contempt of the balance of his race.”16

Once they arrived in New Orleans, the group procured passage for the next leg of their journey—a 500-mile trek to Shreveport. The next day, they boarded a rickety boat that Council described as crowded with “both passengers and property, in consequence of the powerful emigration going on just at that time, from the States of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. The lower deck was literally jambed [sic] full of very poor white people, negroes, mules, and dogs…”17

The journey to Shreveport took three days. Once there, the three men were shocked to discover that they remained 500 miles from Clarksville (by river). Unable to afford to rent horses to make the shorter trip overland, on December 25, they secured passage aboard a boat traveling across what Council called “Soda” Lake, which is probably Caddo Lake.

After a treacherous journey across the lake, they landed at Jefferson and disembarked. Still 100 miles from Clarksville, they rented two horses, for $3 a day, and set out once more. Five days later, on January 30—fifty-two days after leaving Indiana—they arrived in Clarksville.18

Although Council does not reveal many details, upon their arrival in Clarksville they “made a confidential friend, from whom we learned that the object of our pursuit was there, and through the influence of this friend we made another, both of whom proved to be men of influence and integrity.”19 One of these unnamed men could have been the same man who first told John Ryman about Eli Terry. These “friends” were men not only connected to the local community but also who possessed information as to the nature of Council’s purpose and were willing and able to assist. They told Council and his companions “the whole history of the abduction of the negro.”20

This account raises many questions. How did Eli Terry know these men and how did they learn about his story? When did he confide in them?

Ryman, Council, and Harrison arrived in Clarksville in the nick of time. A few days before, Edward West had sold Eli Terry to a man named Chatfield for $800.21 Chatfield, hoping to make a profit, was preparing to take Terry to New Orleans and sell him. If the trio had arrived a few days later, Eli Terry might never have regained his freedom.

Wasting no time, the next morning, John Ryman submitted a writ of habeas corpus to Judge John T. Mills. The sheriff took Eli Terry into custody and brought him to Amos Morrill’s law office.22 Morrill provided invaluable assistance to the freedom seekers.

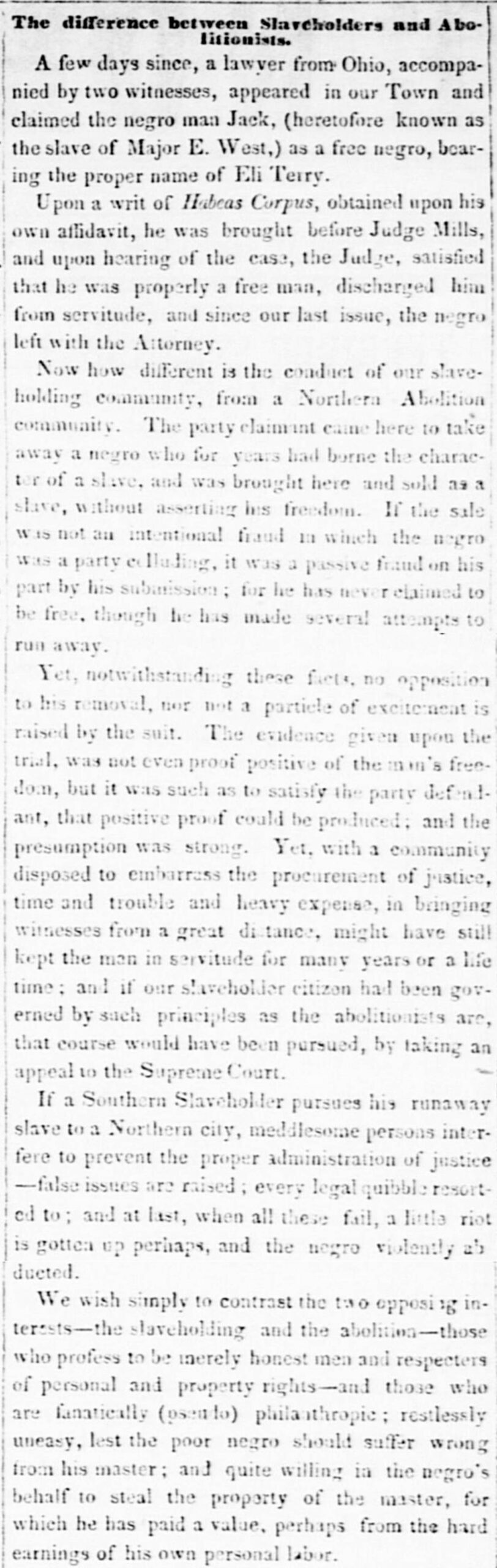

Word spread throughout the community. By the time Ryman, Council, and Harrison arrived at Morrill’s office, it was overflowing with people. Many of the onlookers doubted Eli Terry’s claims to freedom. Surely some believed, as one man who wrote in the Northern Standard, that “the evidence given upon the trial, was not even proof positive of the man’s freedom.”23

Judge John T. Mills, described as a man of great determination with “the ferocity of a wild buffalo when exasperated by the poison dart of an Indian hunter,” interrogated Terry in front of the assembled crowd. Mills asked Terry if he recognized anyone in the crowd with whom he had been acquainted with in Indiana. After searching the room, his gaze fell upon Mr. Harrison and he exclaimed, “there is Mr. Harrison, and he knows I am free.”24

Seeking further confirmation of Terry’s free status, Mills questioned him about his life in Indiana.

RSP/id/7789/rec/1

During Mill’s questioning, a man in the crowd offered to represent the absent West’s interests in the suit. Although West had sold Terry, he remained liable for the contract and would have to refund Chatfield the $800 if Mills deemed Terry to be a free man. Chatfield, for his part, was not inclined to challenge the assertion that Terry was a free man, perhaps because he stood to lose nothing from the determination.

Judge Mills halted what he deemed a “court of inquiry” and remanded Terry into the sheriff’s custody to await West’s arrival. As some in the crowd threatened violence, Mills announced that “he believed the negro was as free as he was.”25

For nine long days, the matter lay undecided. Eli Terry remained in the sheriff’s custody and the three northerners remained wary and lived in uncertainty as to their personal safety.

When the proceedings resumed, Council and Harrison testified on Terry’s behalf. They were examined and cross-examined. West’s attorney delivered a lengthy but ultimately unconvincing pleas. Judge Mills promptly decreed that Eli Terry was a free man.

The judgment did little to settle the crowd. Angry voices threatened to appeal the matter. Ryman, however, was prepared for just such a scenario. He calmly asserted that if West appealed, he intended to prosecute West for Terry’s services “as well as claim damages for every lick they had struck him.”26 This quieted the crowd. Ryman negotiated with West that if he did not appeal the decision, Terry would sign an agreement releasing West of any future claims of wrongful enslavement.

After quick consideration, West agreed.

The group of four men, more than a little concerned for their safety, hurriedly left town. They retraced the path back through Jefferson where they returned the two rented horses. Unable to secure a boat to take them across the lake, they set out for Shreveport on foot. From there, they boarded a boat and made the return trip home.

It is impossible to know what Eli Terry thought and felt while he waited in custody for his future to be determined by a judge who he had no reason to trust would do the right thing. Each day of the eight long years he was enslaved must have felt like a lifetime.

As the group of four men walked, just east of the Texas border in Louisiana, they crossed paths with “a great many negroes,” who were “all on foot, and appeared to be very much fatigued.”27 Crossing paths with this coffle of enslaved people, marched west by slave traders or their enslavers, must have been difficult for Eli Terry to see. As he headed toward freedom, they headed to an uncertain future of enslavement in a new place. Whereas Terry looked forward to being reunited with his family, these men, women, and children mourned their separation from and loss of their family connections.

Endnotes

1 Paul Finkelman, “Almost a Free State: The Indiana Constitution of 1816 and the Problem of Slavery,” Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 111, no. 1 (March 2015: 64-95.

2 “An Act concerning Free Negroes and Mulattoes, Servants and Slaves,” Act of February 10, 1831, chap. 66, The Revised Laws of Indiana (1831), 375-76. See also, Paul Finkelman, “Almost a Free State: The Indiana Constitution of 1816 and the Problem of Slavery,” Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 111, no. 1 (March 2015: 64-95.

3 Indiana state constitution, 1851, Article XIII, section 1. https://www.in.gov/history/about-indiana-history-and-trivia/explore-indiana-history-by-topic/indiana-documents-leading-to-statehood/constitution-of-1851/

4 Council 28-29.

5 Council, 29.

6 Council, 29.

7 The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) January 12, 1850. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/7789/rec/1

8 Pat B. Clark, The History of Clarksville and Old Red River County (1937), 212. H. David Maxey, online editor. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://supsites.tshaonline.org/redriver/pc_cont.htm; Clarksville Original Land Grant Surveys, Texas General Land Office Map of Red River County, 1934). Accessed June 1, 2023. https://supsites.tshaonline.org/redriver/pc_map1.htm

9 Council, 29-30.

10 Council, 30.

11 Council, 30.

12 Northern Standard, January 12, 1850.

13 Indiana American (Brookville, Franklin County, Indiana), February 15, 1850. It’s possible that Ryman mistook or misspelled Walker’s name. Although there are no Walkers in the 1850 census for Red River County, there is a J. M. Wilker, a forty-seven-year-old carpenter. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=IA18500215.1.3&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

14 Indiana American, February 15, 1850.

15 Council, 11.

16 Council, 12.

17 Council, 16.

18 Indiana American, February 15, 1850.

19 Council, 28.

20 Council 28.

21 Council, 30.

22 1850 U.S. Census, Red River County, Texas. Council only identifies the attorney as “Morrel.” Amos Morrill, identified as a 43-year-old attorney worth $2000, resided in Red River County. Morrill was born in Massachusetts, making it probable that he was willing to support Eli Terry’s claim.

23 Northern Standard, January 12, 1850.

24 Council, 31.

25 Council, 32.

26 Council, 33.

27 Council, 34.