Red River County

Charting Routes and Connections

On the Run: Moving Toward Freedom & Family, 1836-1865

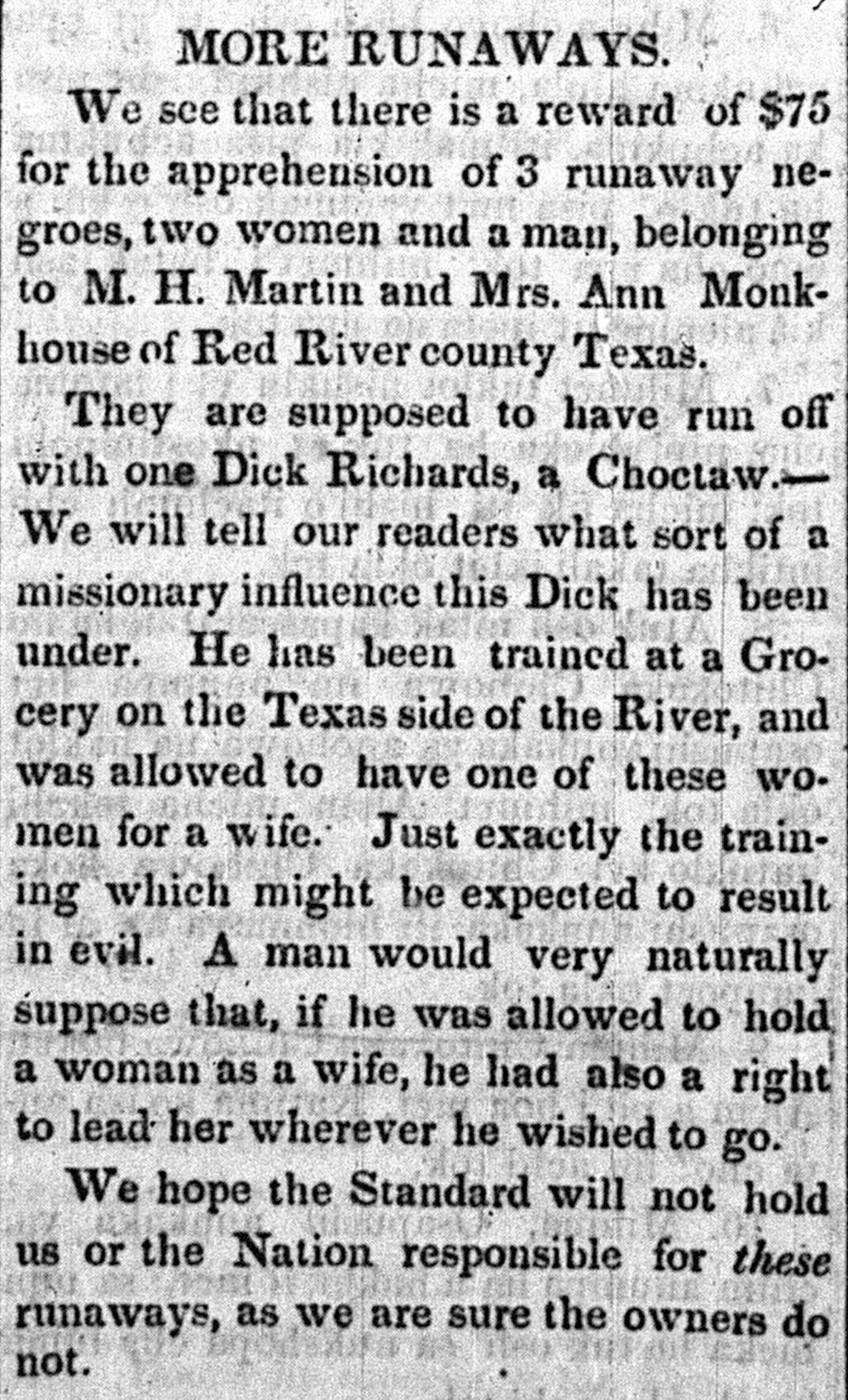

For the men, women, and children enslaved in Red River County, Texas, freedom lay directly north—across the Red River—in unorganized Indian Territory. Newspaper ads seeking information about runaway enslaved men and women attest to their persistent resistance to enslavement and their determination to claim personal freedom. They show a different type of movement—one motivated by freedom—into and through Red River County. Although written from the enslaver’s perspective, runaway slave ads contain revealing information and clues about enslaved people’s lives.

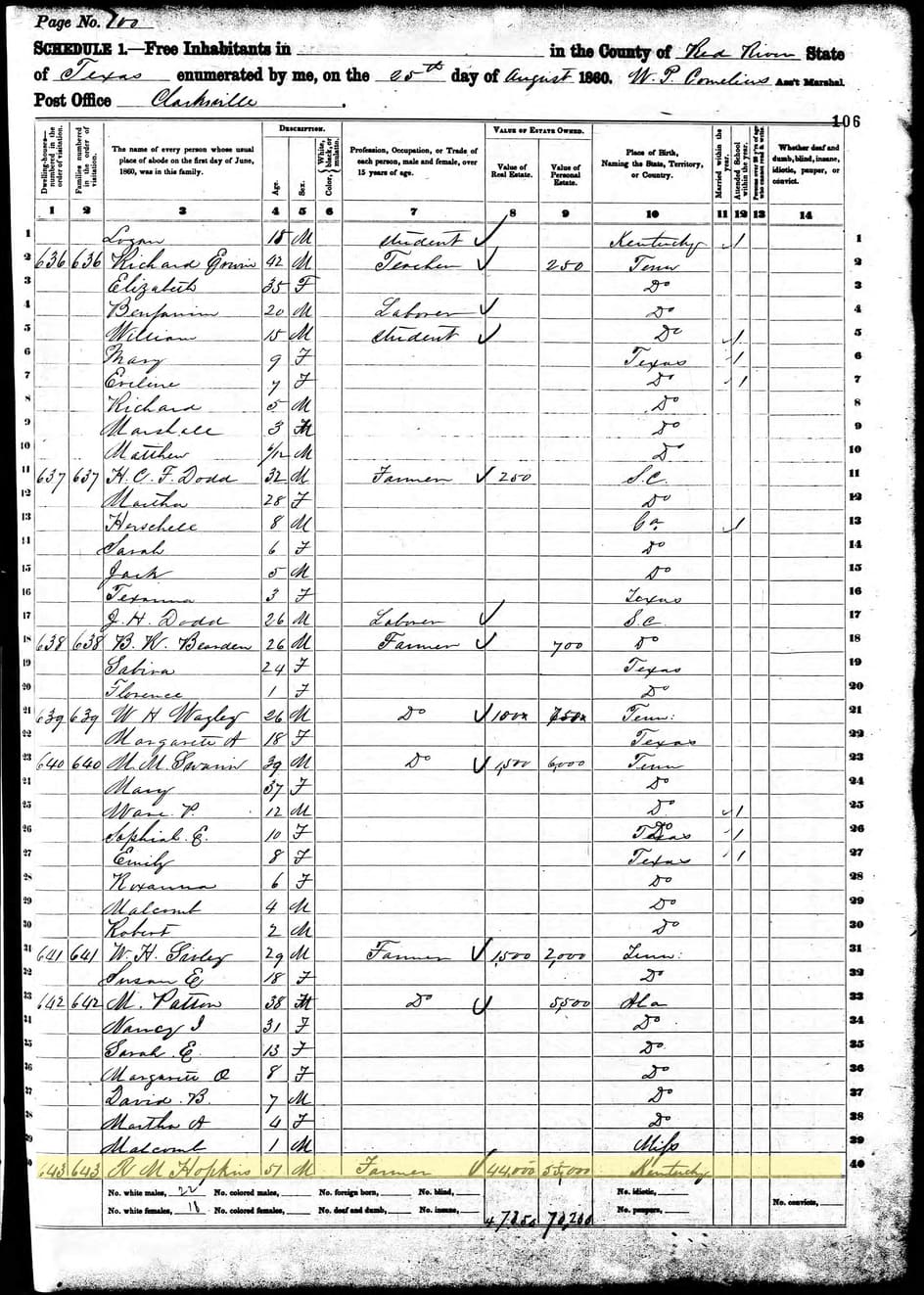

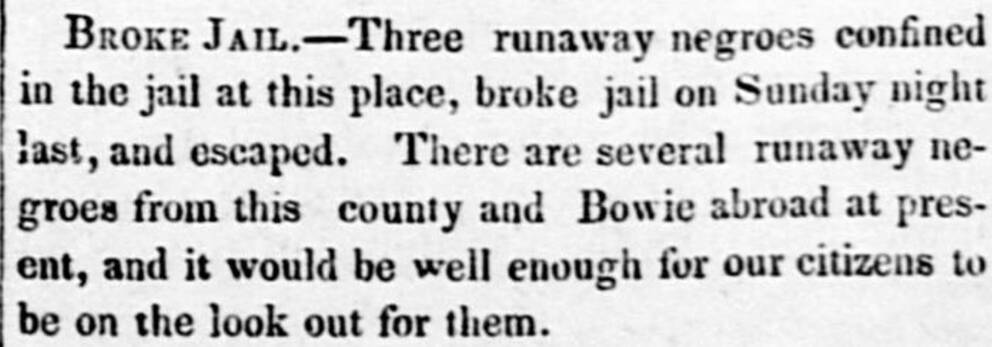

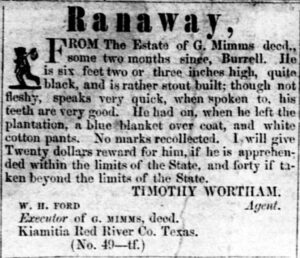

The Northern Standard, March 9, 1843. Portal to Texas History. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth80477/m1/1/

Colonel Charles DeMorse, known as the Father of Texas journalism, started publishing The Northern Standard in 1842. It was the first weekly newspaper in Clarksville—the seat of Red River County—and ran until 1888. The paper grew as the community grew, eventually becoming the newspaper with the second largest distribution in Texas.

In addition to reporting on local, state, and national news, slaveowners frequently placed ads in The Northern Standard seeking information about enslaved people who had run away seeking freedom.

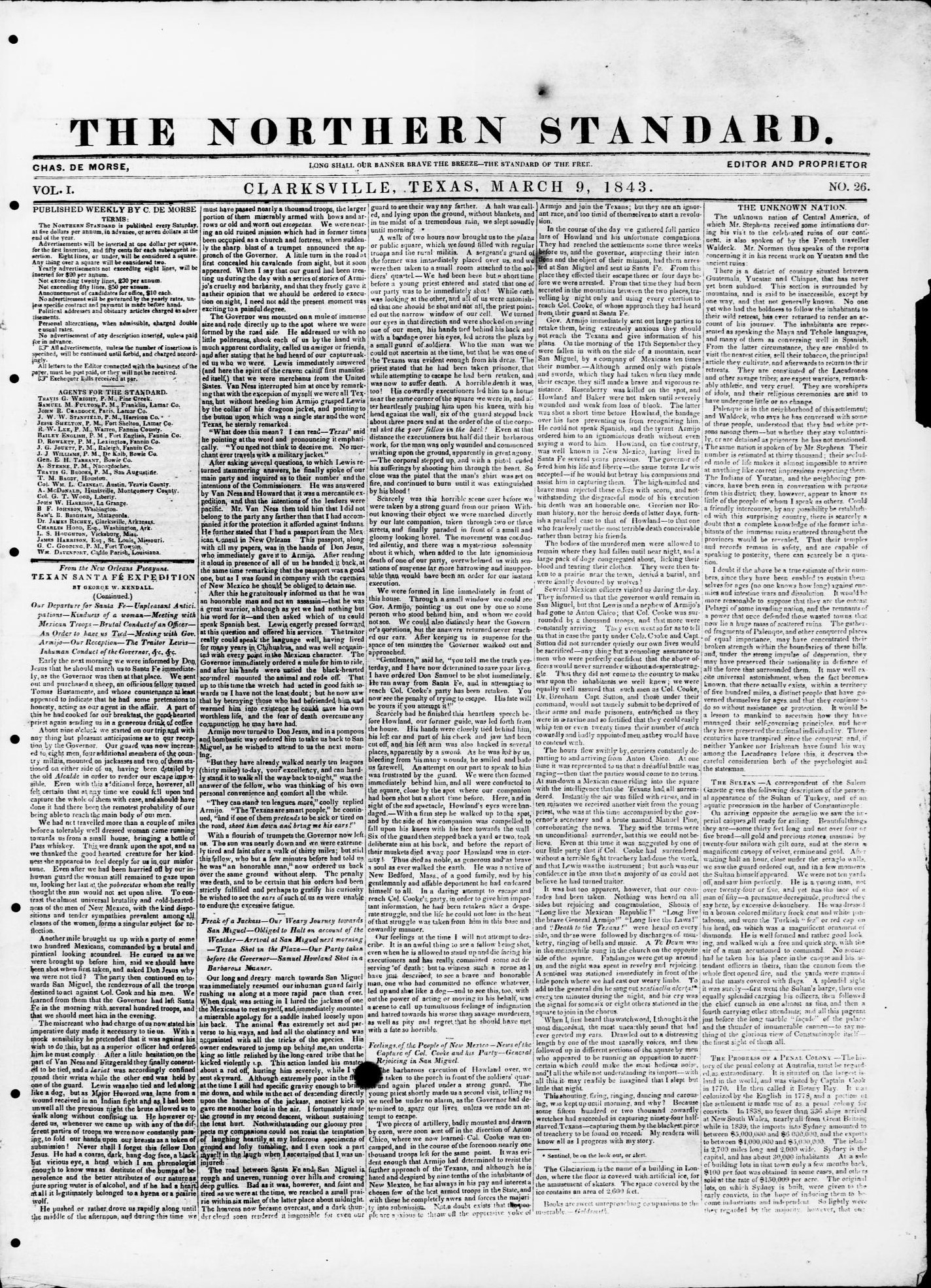

1860 U.S. Census, Red River County, Texas. R.M. Hopkins appears on the last line with $44,000 in real estate and $55,000 in personal property.

Born in Tennessee, Richard Mark Hopkins and his brother James E. Hopkins migrated to Texas in the 1830s. They were among the wealthiest enslavers in Texas. Together, in 1860, they enslaved almost 140 men, women, and children in Red River County.

Enslaved people on the Hopkins plantation primarily grew corn and cotton. In 1860, the Hopkins’ plantation consisted of approximately 1,200 acres of farmland where the enslaved people working it produced 10,000 bushels of corn and 385 bales of cotton.

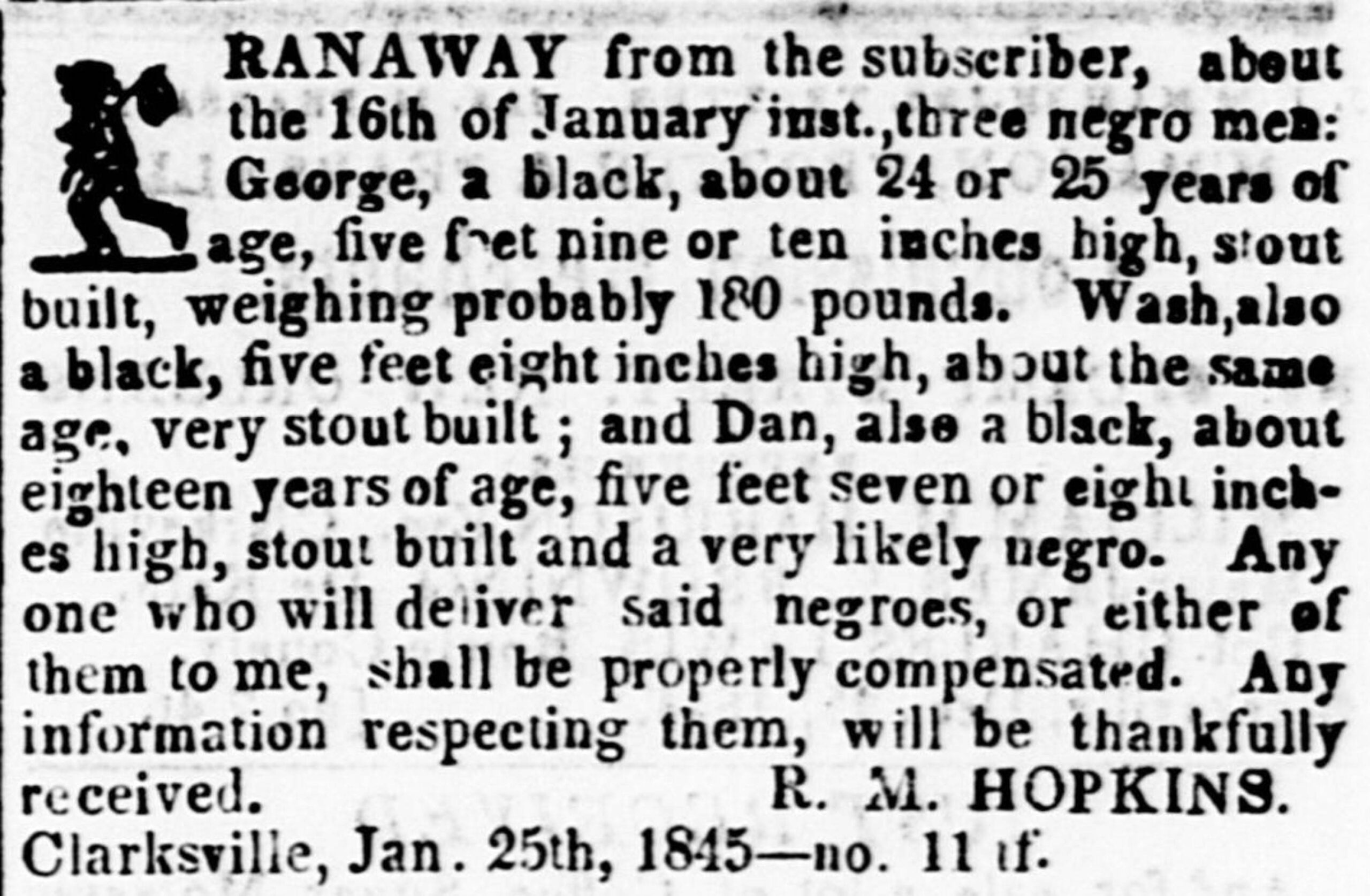

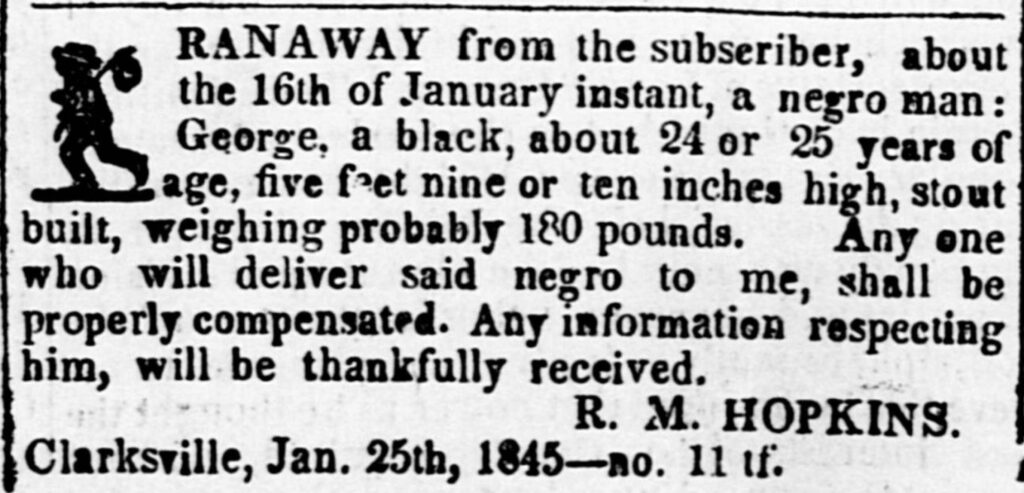

The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) January 30, 1845. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/377/rec/8

Among the 140 people they enslaved were three men—George, Wash, and Dan—who decided in mid-January 1845 to make a run for their freedom.

Like most enslaved people who attempted to self-emancipate, George, Wash, and Dan were men in their late teens to mid-twenties.1

These three men were at the peak of their physical primes. If this was an ad marketing them for sale, they would have been described as “full hands” and they would draw top dollar. Individually, each was extremely valuable to Hopkins, explaining the offer of a reward for their capture.

The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) February 6, 1845. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/4681/rec/12

The fact that George, Wash, and Dan ran away together is important and raises many questions. Were they related? Did they have a common destination in mind—other than freedom? They likely planned their escape together, but the ad does not include any details as to what they took with them that might be used to discern where they might have been heading. It is possible they left the Hopkins plantation and headed north to Indian Territory. Because of Red River’s location in north Texas, one border lay between them and freedom.

This ad appeared in The Northern Standard one week after the previous ad. Hopkins no longer sought Wash or Dan.

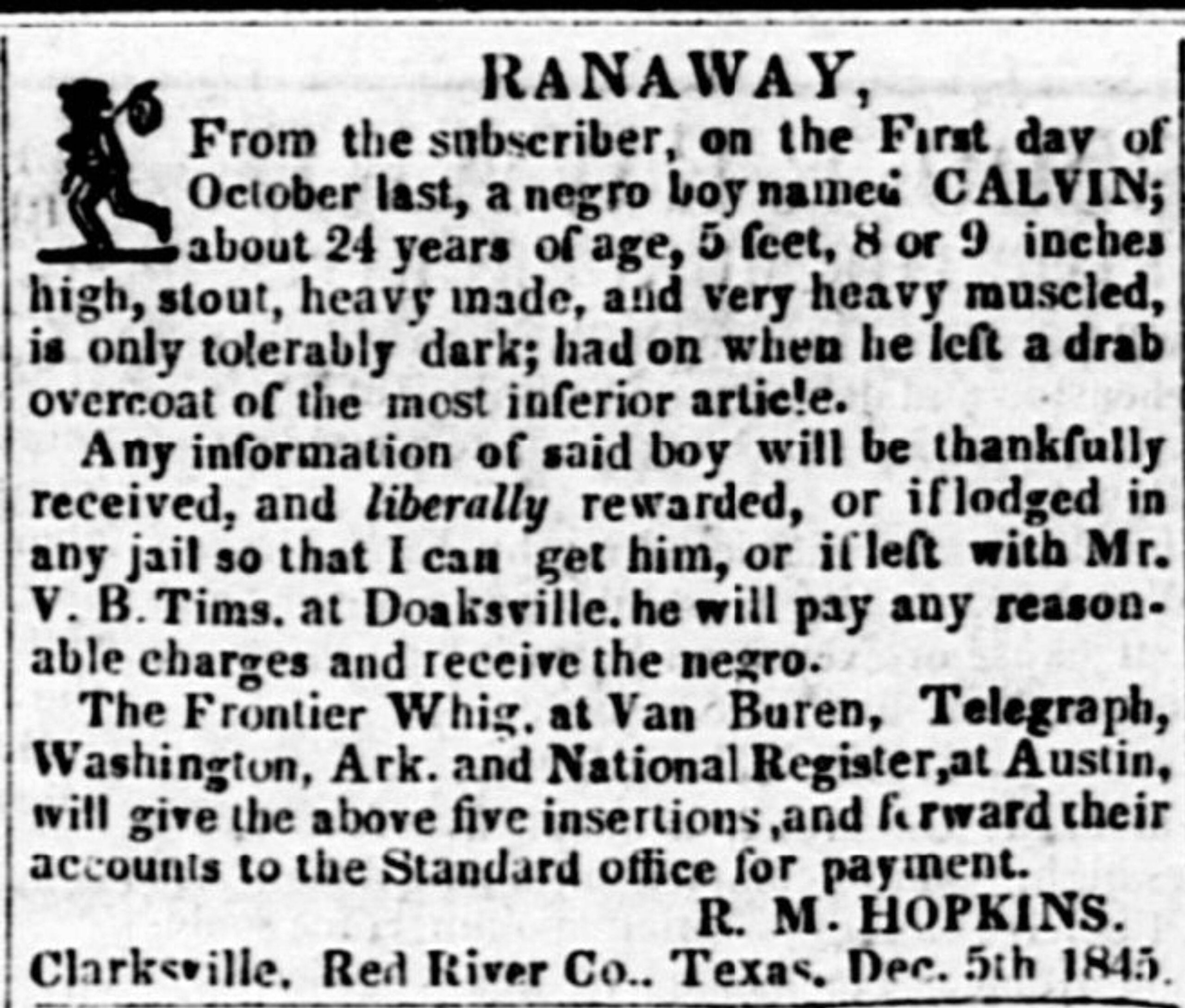

Was George the only one who still avoided capture? Did he make it to freedom? Eleven months later, Hopkins again took to the newspaper in search of a runaway. This time, Calvin, described as 24 years of age and “very heavy muscled” left the Hopkins plantation on his own on the first day of October.

Cotton is typically planted in April and harvested four months later. It’s probable that Calvin left during harvest. Perhaps that gives another possible reason for his decision to leave when he did.

The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) December 10, 1845. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/194/rec/7

This ad reveals another aspect of Calvin’s life. Hopkins detailed that he “had on a drab overcoat of the most inferior article.” If Calvin’s overcoat was “of the most inferior” quality, then that is because that is what Hopkins provided for the people he enslaved to wear. Planters, like Hopkins, generally distributed clothing, shoes, and blankets once a year. And many kept records of each distribution.

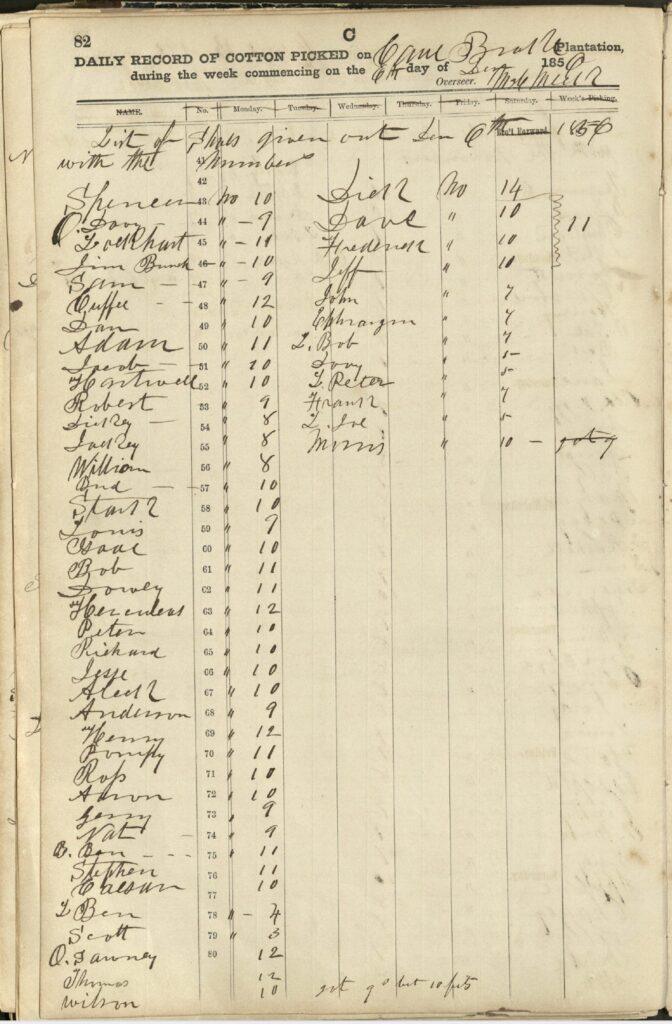

Canebrake Plantation Account Book, 1856. Briscoe Center for American History. Shows the distribution of shoes to enslaved people on December 6, 1856.

Like the previous ads placed for George, Wash, and Dan, Hopkins offered a reward for Calvin’s capture and a promise to reimburse the cost of holding him in jail until such time as he could be claimed. Unlike the previous ads, however, this ad for Calvin reveals two possible directions he likely would have traveled.

Hopkins also placed this ad in both The Frontier Whig in Van Buren, Arkansas, a small town in Northwestern Arkansas, near what is today the Oklahoma border and the Telegraph in Washington, Hempstead County, Arkansas. Washington is on the Southwest Trail, the earliest road across the state, and served as a popular place for those traveling west to pass through. Calvin might have traveled this trail east hoping to reunite with family in Arkansas or Tennessee whom he had been forced to leave behind when Hopkins moved to Texas.

Hopkins also placed the ad in the National Register, published in Austin, Texas, clearly considering the possibility that Calvin might have headed south to freedom in Mexico.

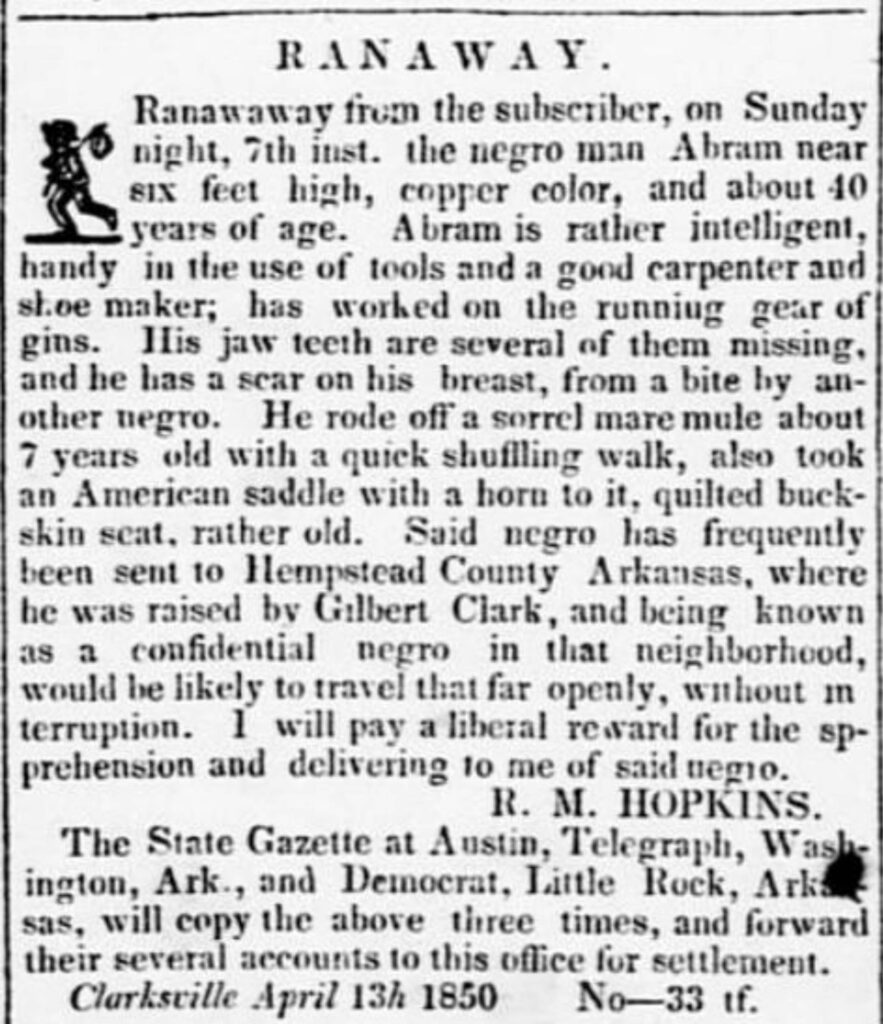

The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) April 27, 1850. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/4337/rec/1

Similarly, this ad Hopkins placed in 1850 seeking the capture or information about Abram reveals much about Abram’s life on Hopkins’s plantation.

Abram did not work in the field like most enslaved people. He possessed specific skills that made him especially valuable—he was a carpenter, shoemaker, and cotton gin operator. Although efficiently planting and picking cotton also required a specific skill set, the skills Abram possessed meant that he was able to perform a diverse range of jobs and would not be limited to laboring in the fields to support himself should his bid for freedom be successful.

Most enslaved people that ran away were young men between the ages of fifteen and thirty.2

In his forties, Abram was older than most enslaved men who ran away. Hopkins deemed him trustworthy enough to send on errands to and from Hempstead County, Arkansas. Because of these travels, Abram possessed specific geographic knowledge that aided in his escape. This knowledge would help him navigate not only the roads, but the people he encountered along the way. Slave patrollers would be familiar with him, enabling him to be able to travel “openly, without interruption.” Abram knew this and used it to his advantage.

Traveling by mule and with a saddle, Abram would be able to cover up to twenty miles a day. In the week in between when he left and when Hopkins’s ad appeared in the newspaper, Abram could be 140 miles away from the Hopkins plantation. This explains why, in addition to the local paper in Clarksville, Hopkins placed ads in newspapers in Austin, Little Rock, and Washington County, Arkansas.

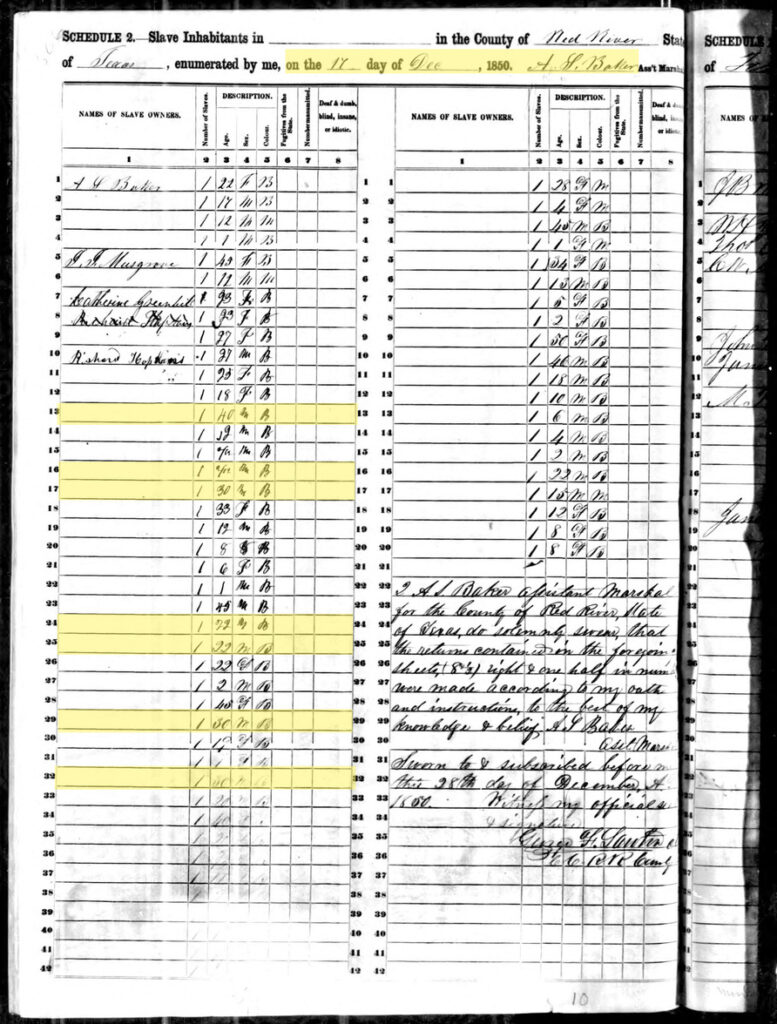

1850 Slave Schedule Red River County, Texas. Lines 17, 29, 32, could be George, Wash, or Calvin who would have been 29-30 years old in 1850. Dan would have been 22-23 and might be the person in the first column, line 24 or 25 or on the second column, line 16.

Not only does this ad provide details about Abram’s skills and intelligence, but it also gives a physical description that reveals something of consequence. Abram had a scar on his chest from a physical altercation with another enslaved person. Within large, enslaved communities, like the Hopkins plantation, enslaved people experienced the same interpersonal conflicts as anyone else. Although we cannot know what caused the altercation, we know it left Abram physically scarred. Hopkins makes no mention of other scars, like those left by the whip or from branding. This omission suggests that Abram avoided the physical violence most enslaved people experienced daily, or that Hopkins chose not to acknowledge any scars he inflicted on Abram. Abram’s ability to travel on his own signifies an elevated position within the plantation hierarchy, which helps us understand how he navigated interpersonal relationships with his enslavers and likely did not experience the same kinds of violence others did.

It is unknown if Abram’s escape was successful. One enslaved man, described as a forty-year-old Black man, appears on the 1850 Slave Schedules among the people Richard Hopkins enslaved. It is possible that Abram had been captured and returned.

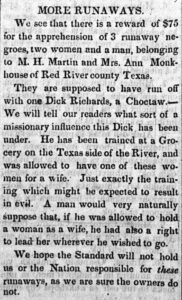

The ads placed by Richard Hopkins, and the ones that follow, placed by other slaveholders, demonstrate that enslaved people in Red River County were constantly on the move and in pursuit of freedom.

It is unclear if these runaways knew each other before their escape or simply worked together to pursue freedom once again.

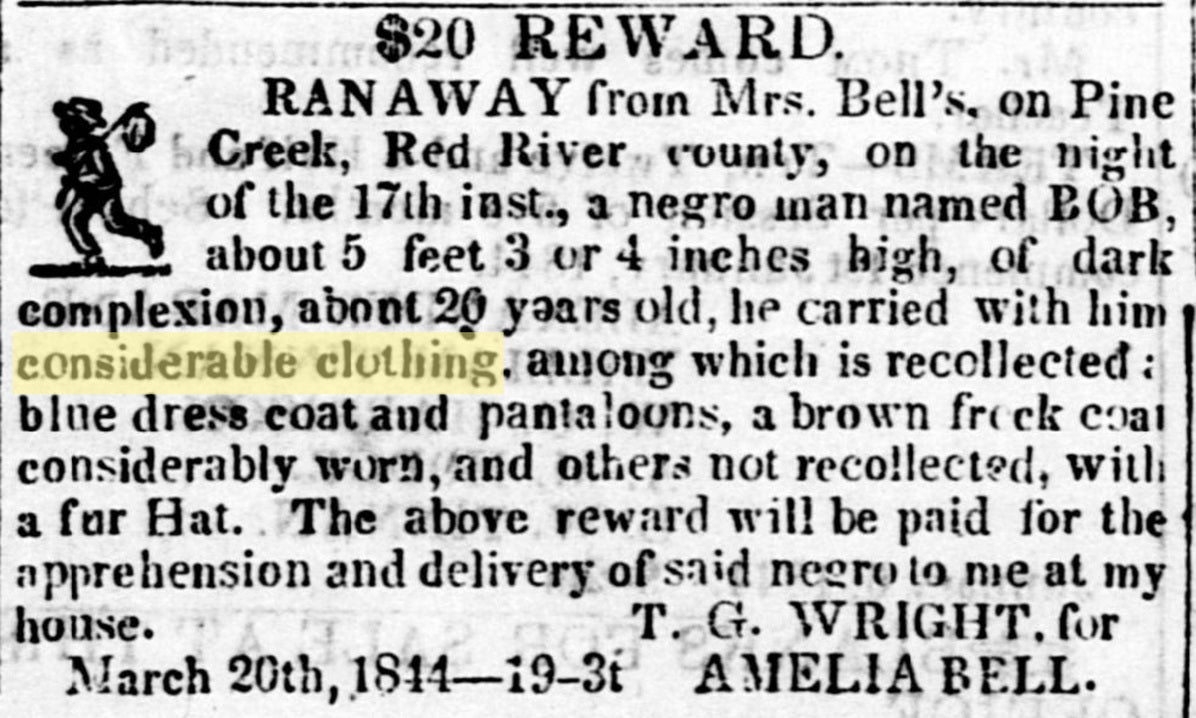

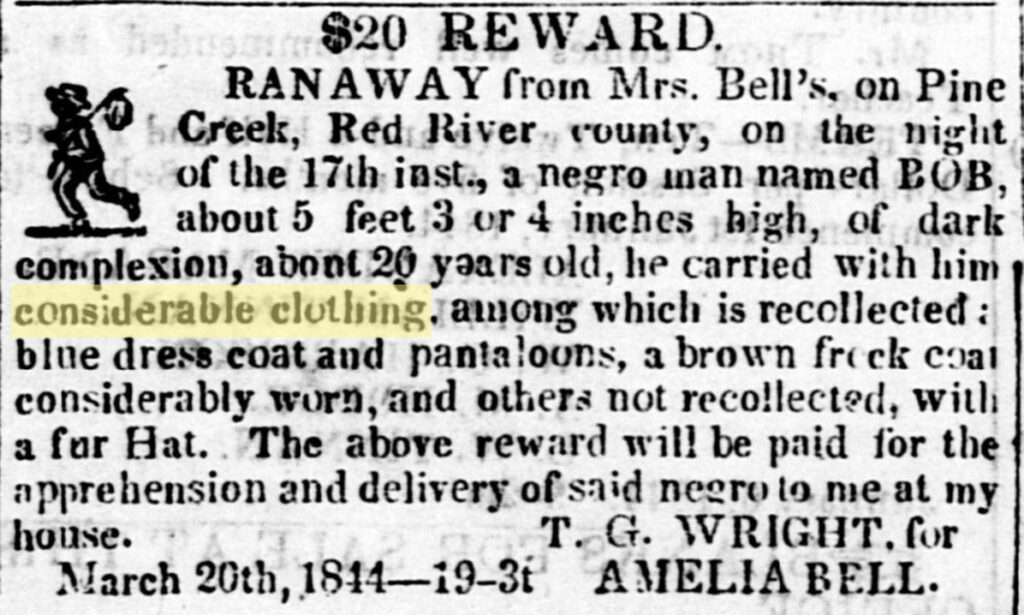

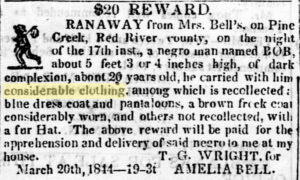

The Northern Standard (Clarksville, TX) March 20, 1844. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/430/rec/3

The fact that Bob brought “considerable clothing” with him, suggests that he planned to be gone for a long time. The fact that he took multiple coats combined with a fur hat indicates that he might have considered trading these items for supplies or planned to go somewhere with a cold climate.

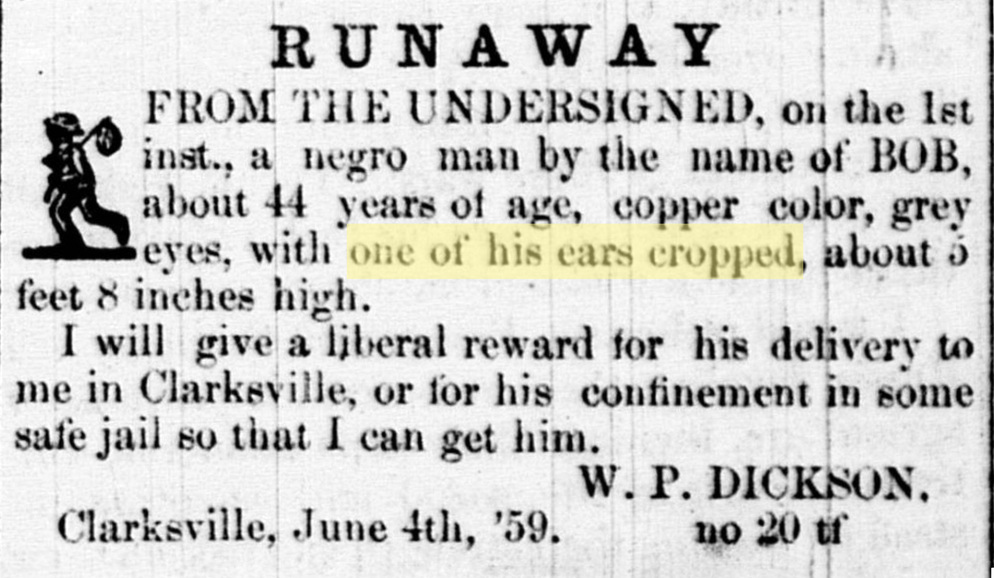

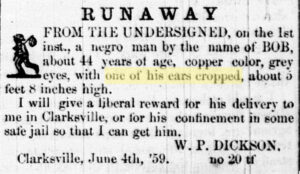

The Standard (Clarksville, TX) June 4, 1859. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP/id/525/rec/4

In addition to Bob’s physical description, this ad reveals something else about his life. An enslaved person might have their ears cropped as a form of punishment for any number of “transgressions,” including theft and lying. An enslaved person accused of a crime might be prosecuted in court or might have simply been punished by the enslaver—without any formal hearing, trial, or process.

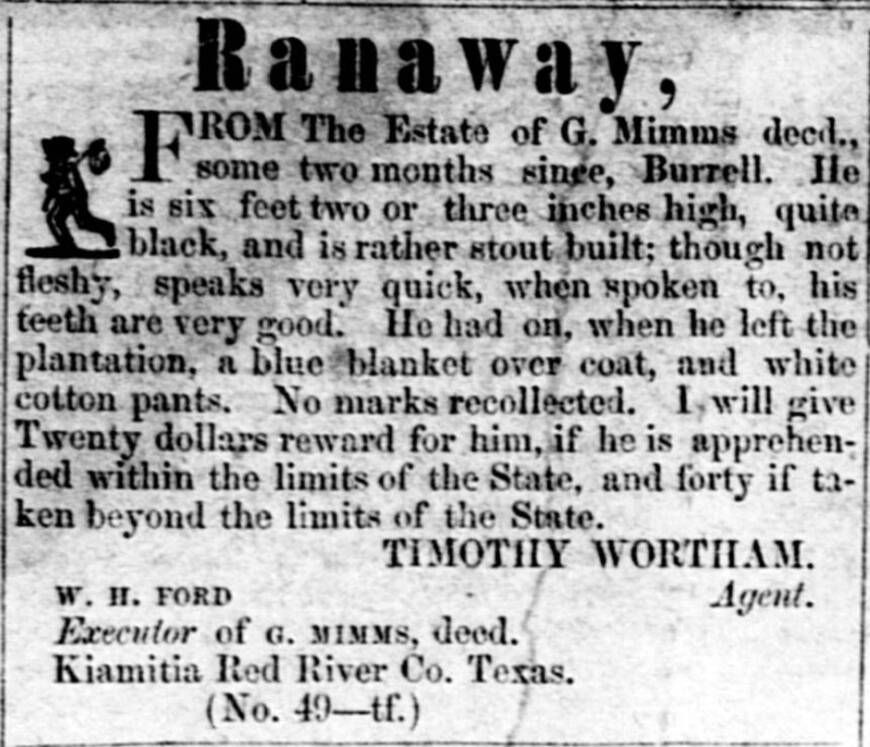

Burrell, perhaps making the most of the opportunity his enslaver’s death provided, escaped with the clothes on his back. At the time of the ad, he had been gone for two months, likely headed out of state. Indian Territory would have been the closest option, but freedom was not guaranteed there as many indigenous groups participated in the domestic slave trade, selling enslaved people they captured or kidnapped.

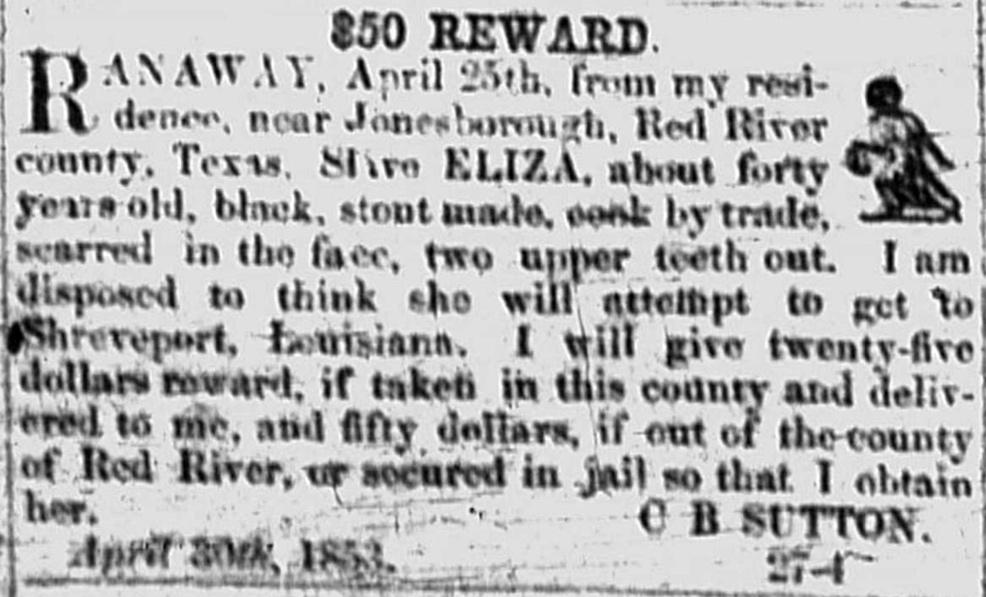

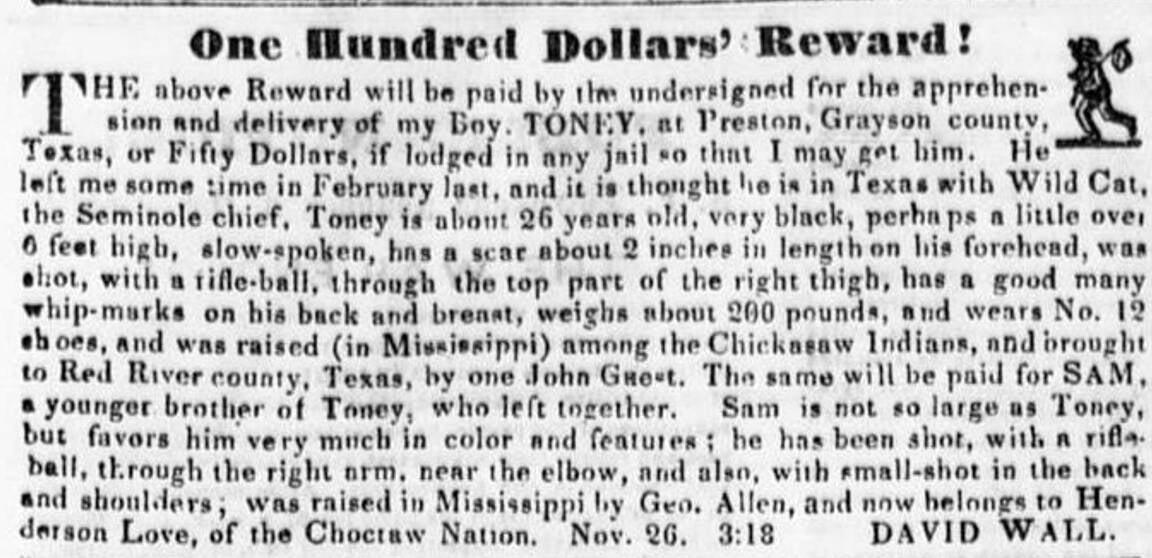

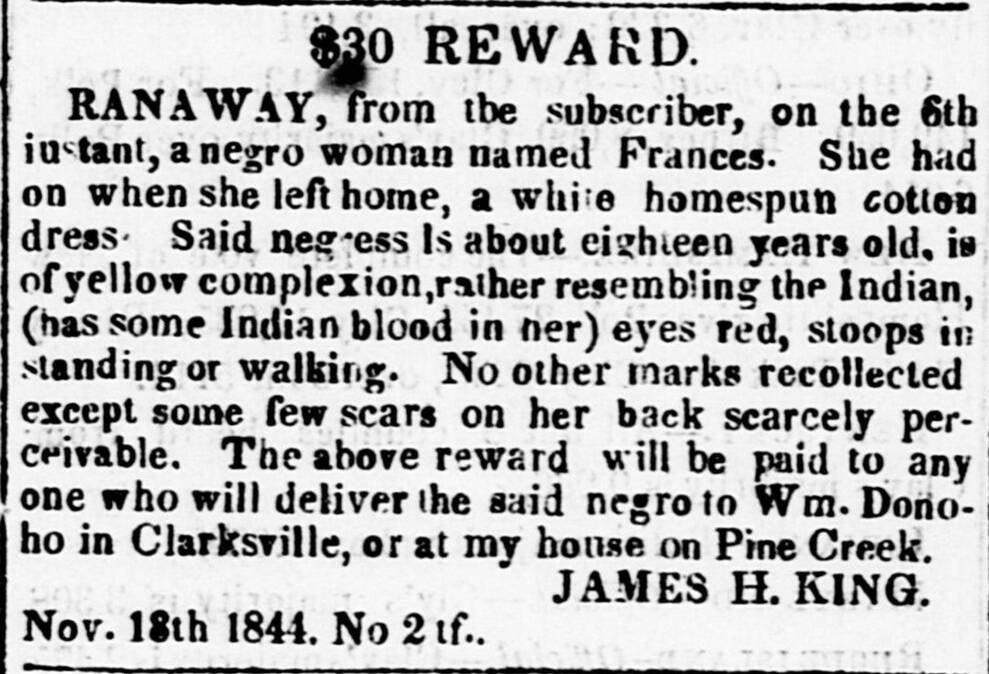

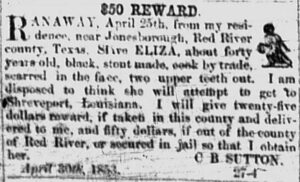

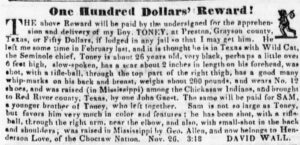

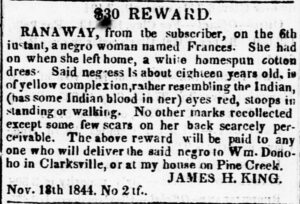

HEADING FOR SLAVE AD CAROUSEL

1 For more information on runaway slaves, see: John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Alice L. Baumgartner, South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 2020); and Stephanie M.H. Camp, “I Could Not Stay There’: Enslaved Women, Truancy and the Geography of Everyday Forms of Resistance in the Antebellum Plantation South,” Slavery & Abolition vol. 23, no. 3 (December 2002): 1-20.

2 Ibid.