Red River County

Charting Routes and Connections

Lives of the Enslaved in Red River County: Interviews with Harriet Jones and Mose Hursey, 1936-8

Enslaved people left little evidence detailing their daily lives. The most common records documenting slavery and the lives of the enslaved are records created by the enslavers—census records, plantation account books, court records, auction broadsides, runaway slave ads, and bills of sale.

Although these records provide some insight into enslaved people’s lives, they are all filtered through the lens of the white people who created them. Seldom do we find enslaved people’s experiences expressed in their own voices. Information wanted ads, ex-slave narratives, and interviews conducted by writers for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1936-1938 are the exception. Even so, each of these records come with their own sets of challenges. Lapses in memory, misremembered details, the frequency of changed names, multiple dislocations—in addition to the extreme trauma many enslaved people experienced daily—complicates how historians use these sources. Despite the challenges, these sources reveal aspects of enslaved people’s lives available nowhere else.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs included the Federal Writers’ Program designed to employ unemployed writers during the Great Depression. The Works Progress Administration—later renamed the Work Projects Administration in 1939—focused on documenting elements of American folklore and interviewing and compiling anthologies of the lives of Americans from diverse backgrounds. Out of this initiative a project dedicated to interviewing and publishing the first-hand accounts of formerly enslaved people was born. The WPA collection includes almost 2,400 interviews with formerly enslaved people throughout the South. For more on the background of the WPA narratives, visit the Library of Congress site The WPA and Slave Narrative Collection.

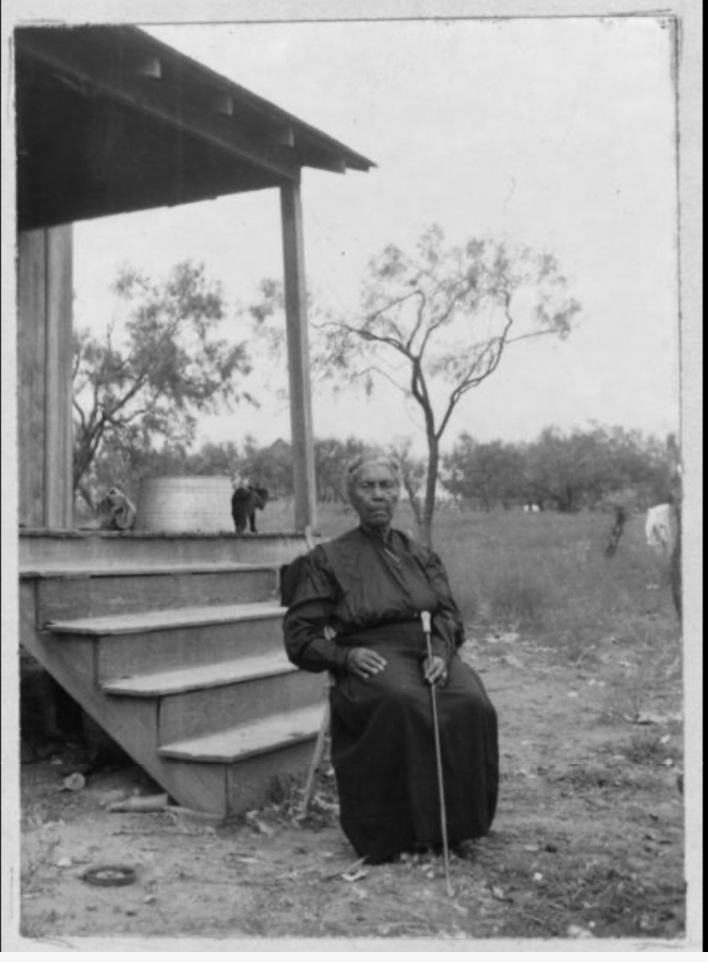

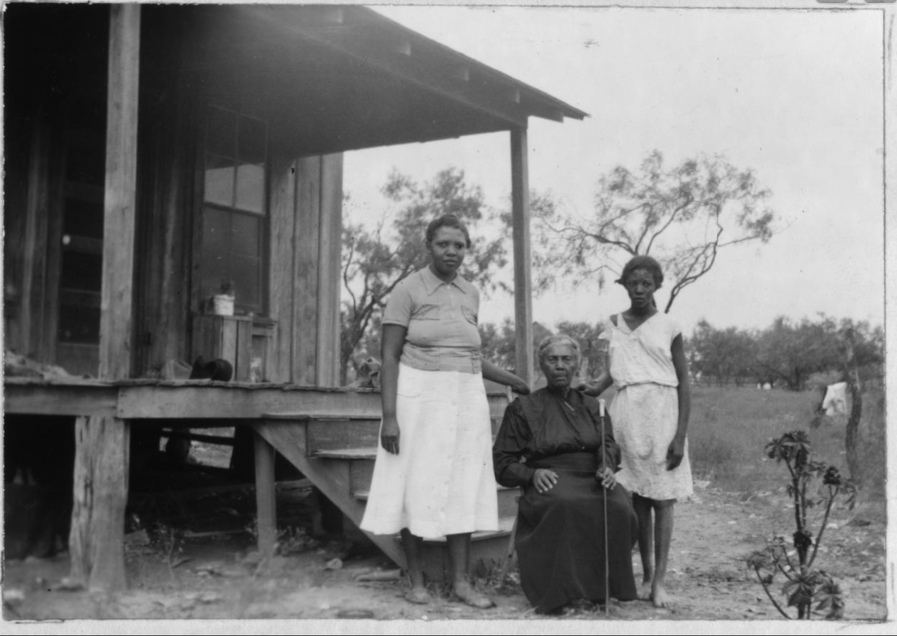

Harriet Jones

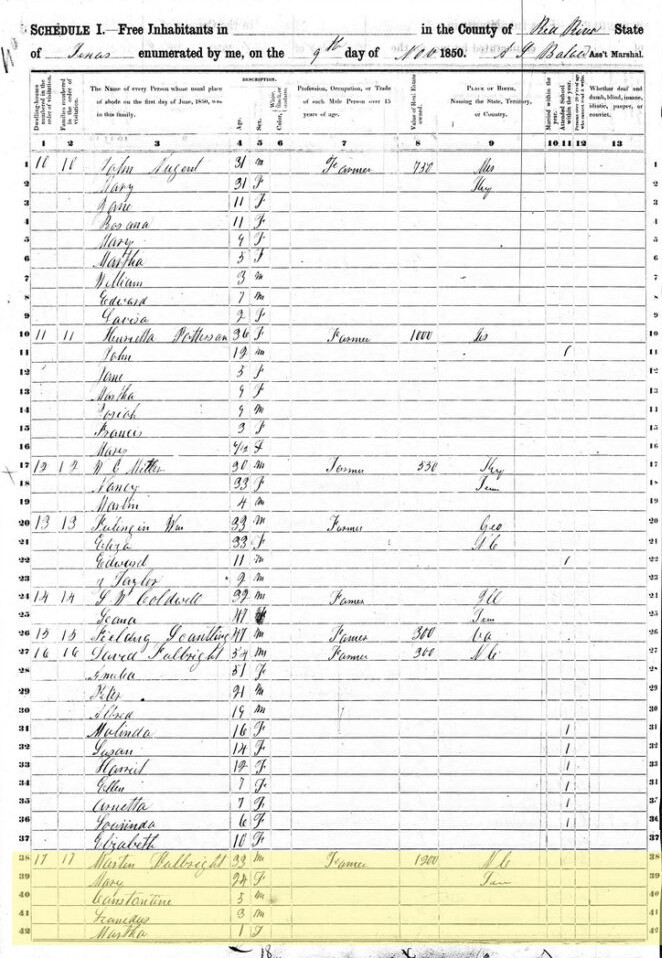

Martin Fulbright brought Harriet Jones’s parents, Henry and Zilphy Guest, to Red River County, “long ‘for freedom.”

Born in 1844, the year before Texas became a state, Harriet Jones recalled that like many farms and plantations in Red River County, the Fulbrights grew corn, oats, and cotton and raised cattle, hogs, sheep, and horses.

Harriet’s recollections provide insight into what life was like for enslaved people in a small slaveholding household—households with fewer than ten enslaved people—in Red River County.

In small slaveholding households, life was much different than it was for people enslaved on large plantations. In these confined spaces, enslaved people worked and lived alongside their enslavers—often occupying the same physical space inside and outside of the house. In this environment, enslaved people experienced higher levels of surveillance than those on large plantations where separate slave quarters created a physical and psychological distance between the enslaved and enslaver.

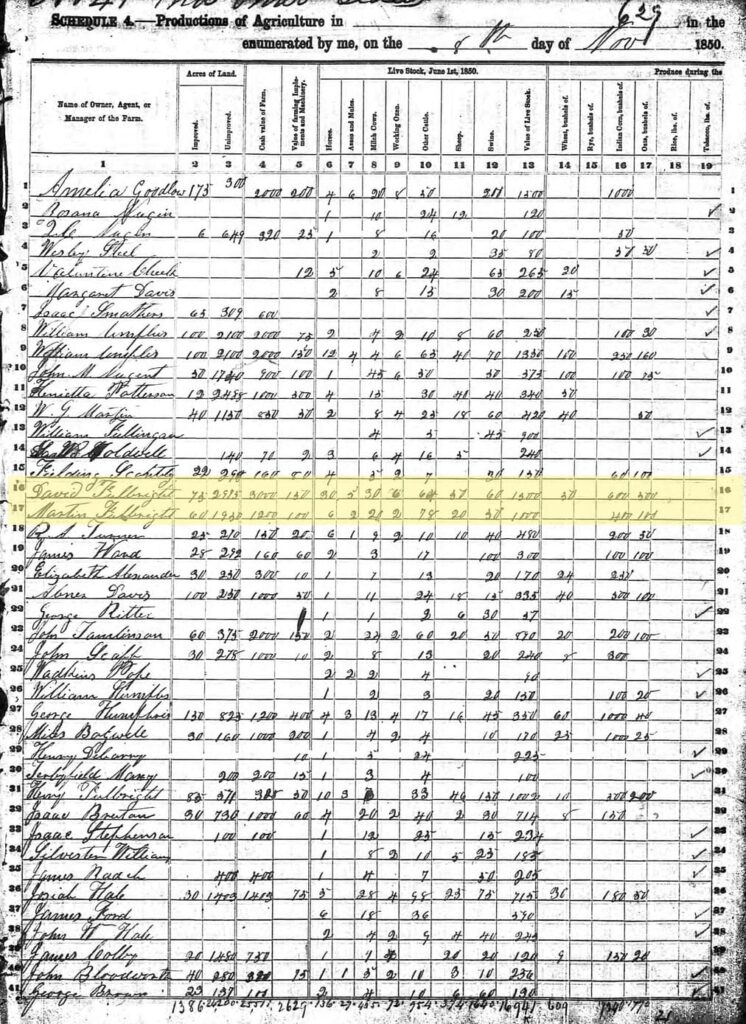

David Fulbright is identified in the 1850 census as a 54-year-old man. He might be Martin Fulbright’s father or older brother. The two men lived on adjoining farms and likely combined resources to plant and harvest their crops.

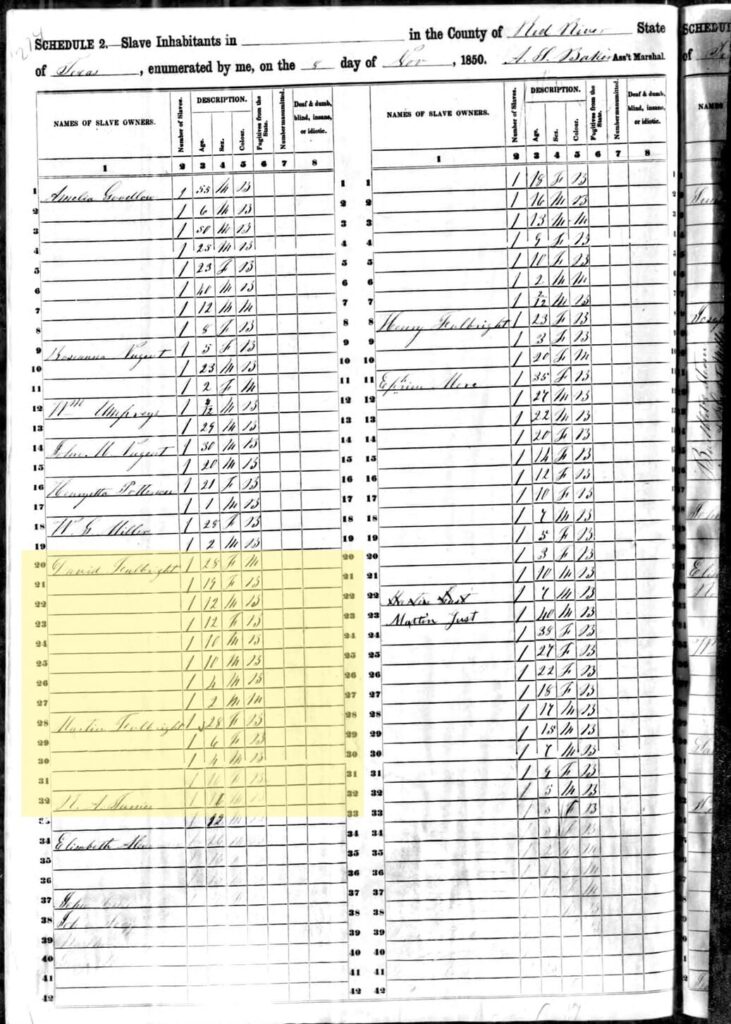

Many census takers listed enslaved people in family groups according to age. This page from the 1850 U.S. Slave Schedule (seen on the left), shows that Martin Fulbright enslaved four people: a 28-year-old Black woman (Harriet’s mother Zilphy), a 6-year-old Black girl (Harriet), a 4-year-old Black boy (Harriet’s brother), and an unrelated 16-year-old Black boy.

Harriet would have begun to perform small tasks at an early age. She might have carried water to the people working in the fields, helped in the kitchen, and cared for her younger brother.

She also likely helped care for the Fulbright’s young children—they had four children under the age of six in 1850, including 1-year-old twin girls.

Enslavers often assigned young, enslaved children with the task of minding the younger children within the household. It was not uncommon for many formerly enslaved people to recall being able to play with all the children in the household until they reached the age where their enslaver assigned them more productive labor.

Many enslaved children began working in the fields around 6-years-old, the age Harriet was in 1850.

As she grew older, Harriet recalled that she worked in the house cooking, knitting, and sewing.

She remembered that “For everyday cookin’ we has corn pone and potlicker and bacon meat and mustard and turnip greens and good, old sorghum ‘lasses. On Sunday we has [sic] chicken or turkey or roast pig and pies and cakes and hot, salt-risin’ bread.” In the South, “potlicker” refers to the liquid left in the pot after cooking items like collard greens and pork fat. No doubt, her mother, Zilphy, brought the recipe for the salt-rising bread that Harriet recalled eating from North Carolina. Native to the Appalachian region, salt-rising bread is made without yeast, using bacteria that grow on grains for fermentation to make the bread rise. As with family histories, recipes were often passed down orally from one generation to the next.

Harriet’s skill with knitting needles helped provide for her and her family. “All us house women larned [sic] to knit de socks and head mufflers,” she said, “any many is de time I has went to town and traded socks for groceries.”

Not only did Harriet go to town to trade for groceries, but she also remembered “huntin’ with de boys, for wild turkeys and prairie chickens, but dey like bes’ to hunt coons and possums.” The fresh meat Harriet remembered eating on Sundays was provided by the enslaved men and women to supplement the meager fare the Fulbrights provided.

For enslaved people in the Fulbright household, the workday in the hot summer months began before dawn when Martin Fulbright blew a horn at four o’clock in the morning to rouse everyone.

They would have spent long, hot days working Fulbright’s sixty acres of farmland. It is possible that Fulbright worked alongside them. Fieldhands would have worked until sometime midday, when the horn blew again to signal the lunch break. In the spring and summer months, the workday would have continued well into the evening, as long as daylight lasted.

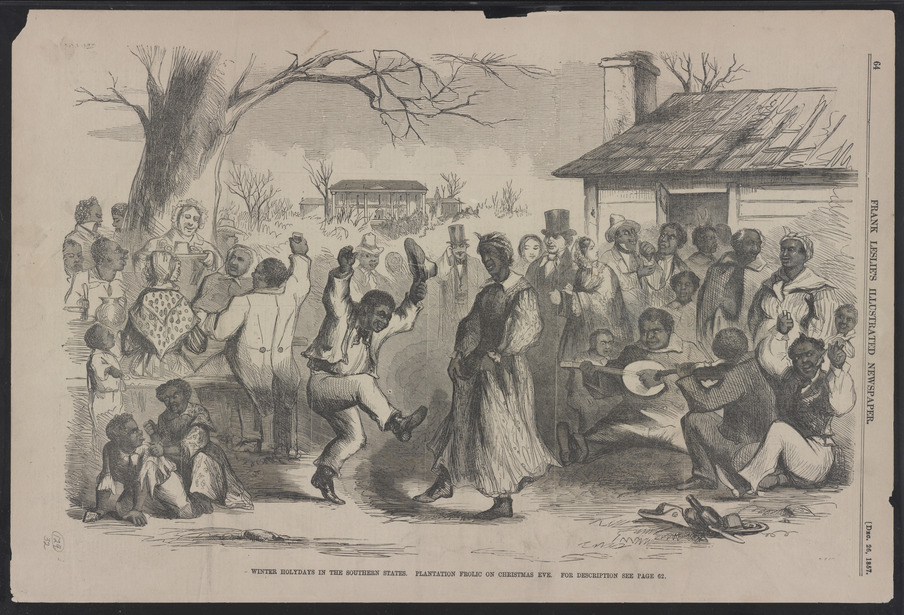

Many formerly enslaved people remember celebrating Christmas. Except for Sundays, Christmas was often the only time of year enslaved people were not expected to work. Depending upon the household, they might get a week’s reprieve from work or just the day. The day itself, however, was often marked by a large celebratory shared meal and sometimes singing and dancing. Harriet’s memories of the Christmas celebrations in the Fulbright household are like many other accounts. According to Harriet, Ellen Fulbright decorated a Christmas tree and hung up stockings for all the children so that the “nex’ mornin’, everybody up ‘fore day and somethin’ for us all, and for de men a keg of cider or wine on de back porch, so dey all have a li’l Christmas spirit.”

The Fulbright’s extended family likely gathered together to celebrate the holiday. This meant that the people they enslaved also gathered together. Harriet described the day in detail. “After de white folks eats, dey watches [sic] the servants have dey dinner.” There were few times in her life that she remembered a meal as good as what they were allowed on Christmas. The Fulbrights brought their children to the slave quarters to watch them eat and dance. As Harriet recalled, “Fore de dance dey has Christmas supper, on de long table out in the yard in front de cabins, and have wild turkey or chicken and plenty good things to eat.” Then they built a fire, moved the table and danced to fiddle and banjo music. The celebrations lasted through the night, “De old marse lets dem frolic all night and have nex’ day git over it, ‘cause its [sic] Christmas.”

From Harriet’s recollections it seems as if the Christmas celebrations included enslaved people from many households in Red River County.

After emancipation, Harriet married a man named Bill Jones and for at least one year, remained with Ellen (Fulbright) Watkins.

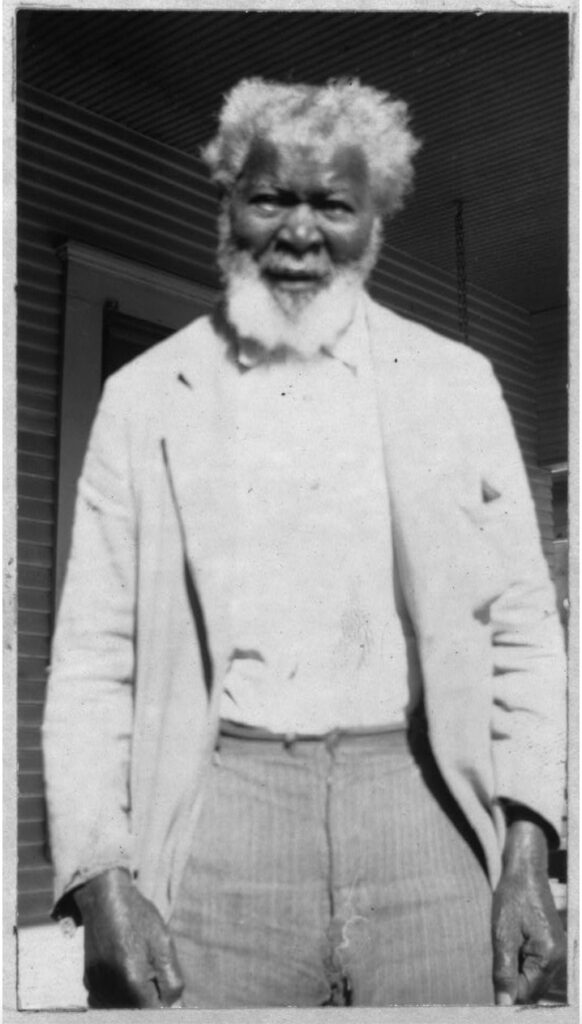

Mose Hursey Remembers His Childhood in Red River County

Mose Hursey, Works Progress Administration, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/ppmsc/01100/01124u.tif

Born in Louisiana, Mose Hursey was just a child when he was brought to Texas. His recollection reflects the oral tradition through which many enslaved families passed down family history from one generation to the next. Hursey remembered that he “heard my mother and father say they belonged to Marse Morris,” who eventually sold Hursey’s family to Jim Boling of Red River County. However, Morris did not sell the entire family–Hursey’s brother and sister remained behind in Louisiana.

Hursey’s family grew after they arrived in Red River. His parents had two more children, and he remembered his time as a young child when he “played ‘round the place,” and as most enslaved children, “wore shirttails … until I was a big boy.”

His family lived in a log cabin and on some Sundays they had gatherings where members of the enslaved community came together to “preach and pray and sing – shout, too.”

Religion played an important role in the lives of many enslaved people. Hursey recalled that members of the congregation were moved “with a powerful force of the human spirit, slappin’ they hands and walkin’ round the place. They’d shout, ‘l got the glory. I got the old time ‘ligion in my heart.’”

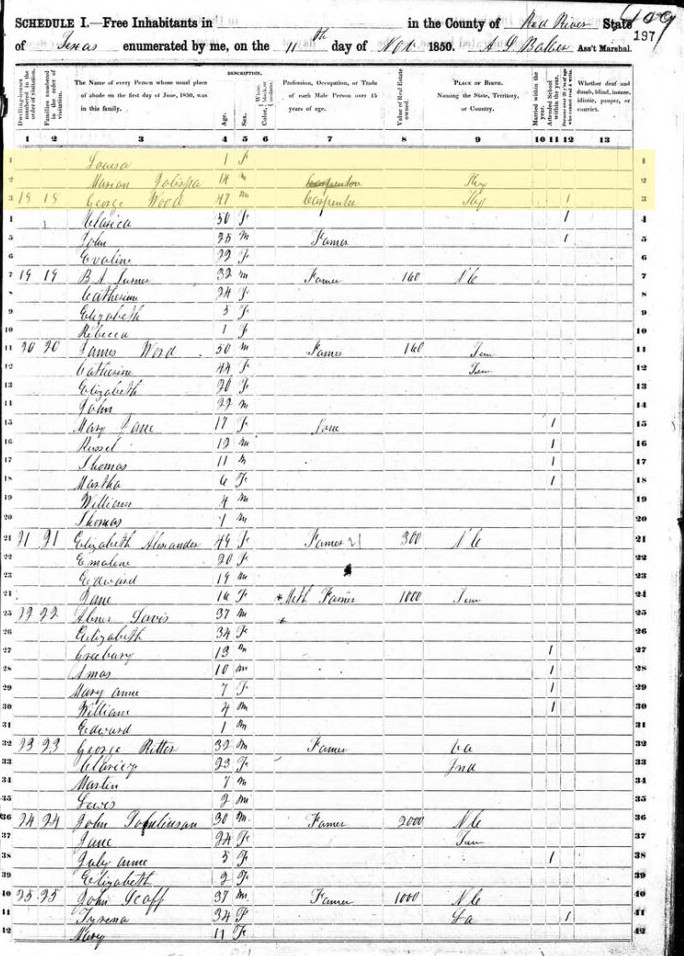

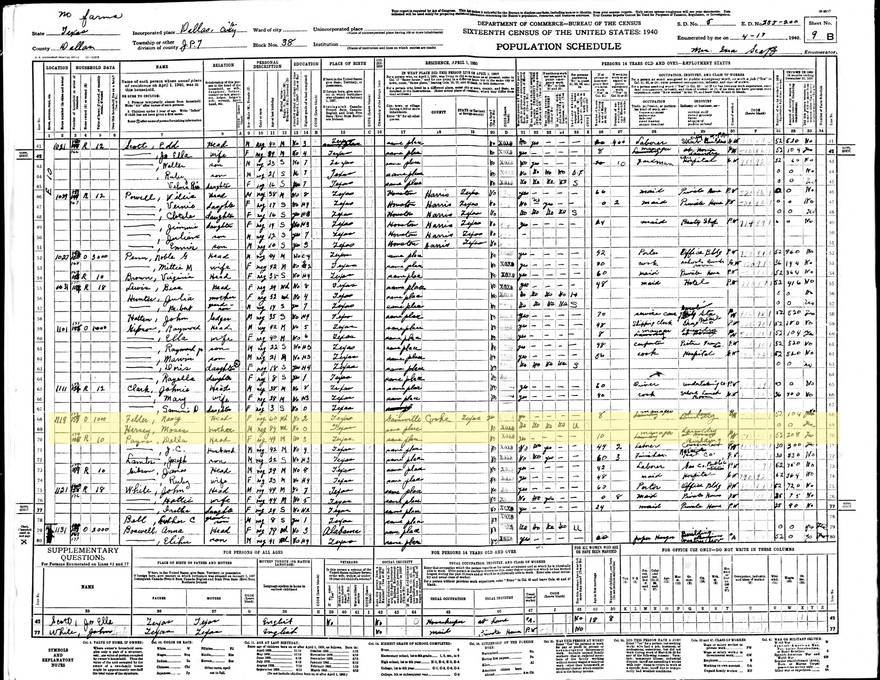

1940 U.S. Census, Dallas, Dallas County, Texas. In 1940, Hursey lived with his sister in Dallas.

Even though he was young, he remembered the words to one popular song that emphasized their common struggle and hope for salvation:

“‘Sisters, won’t you help me bear my cross,

Help me bear my cross,

I been done wear my cross.

I been done with all things here.

‘Cause I reach over Zion’s Hill.

Sisters, won’t you please help me bear my cross,

Up over Zion’s Hill?”