Red River County

Charting Routes and Connections

Methodology: Mapping Movement

Red River County’s geographic location on the southern banks of the Red River in the northeast corner of Texas meant that for enslaved people, freedom existed beyond a single border. Crossing that border might mean moving into slavery, as it did for Eli Terry, or for some, like George, Wash, and Dan, crossing that boundary represented potential freedom. Still, for others, it meant separation from family and loved ones. Thinking about these multiple meanings of movement—into and out of slavery—frames the approach to examining slavery in Red River County.

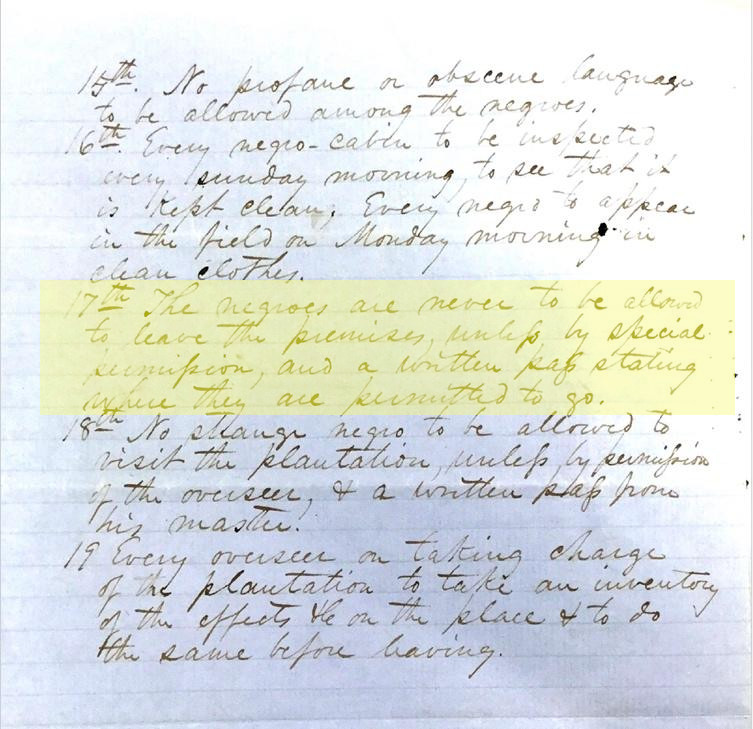

Runaway slave advertisements, the most common records that document enslaved people’s movements and resistance, illustrate how enslaved people understood the geographic boundaries of their captivity—they ran toward freedom or family and away from enslavement. Whereas runaway advertisements represent freedom seeking in various forms, Last Seen advertisements demonstrate forced migration and family separation through the domestic slave trade into Red River County. Combined with Works Progress Administration (WPA) interviews and census records, these sources show how slavery was mapped onto the terrain, creating what historians have described as a system rooted in a “geography of containment” where enslavers held enslaved people captive. To maintain this system of confinement, they established and enforced curfews, required that enslaved people receive permission to leave the premises, mandated that enslaved people carry passes, and enacted systems of surveillance that included random nighttime checks, nightly slave patrols, and weekly inspections of their homes.

Enslaved people resisted these constraints. They ran away, sometimes repeatedly. At night, they left the plantations and farms where they were enslaved to attend prayer meetings, visit loved ones, and claim space for themselves. Thus, movement and geography shape each account of what slavery and resistance looked like in Red River County.