Washington County

Exploring Slavery and its Afterlives

Slavery and Freedom: The Experiences of Enslaved People on the Seward Plantation, 1850-1870

Over the course of the 1850s, the population–free and enslaved–in Washington County increased dramatically. The United States Census counted 5,983 people, including 2,817 slaves, in Washington County in 1850.1 By 1860, there were 15,215 people living in Washington County; the 7,941 enslaved people made up more than half of the population. The population was not the only thing that grew. Farmland had expanded to encompass 365,000 acres, including more than 76,000 acres of improved land.

Enslaved peoples’ experiences in Washington County were not the same, they varied based upon their workings circumstances and most importantly the temperament of their owners. For instance, Lucy St. Cyr, a light-complected enslaved woman owned by a Methodist minister, Boykins Shipman, due to her skin color was able to work inside the main plantation house.2 Lucy stated, “Being very fair complexion with long hair and therefore different from her other sisters,” she became a favorite and was kept in the big house with the master’s family.3 She recalled, “Living in the house with her master she was treated just like the other members of his family, eating at the table with them and wearing the same kind of clothes.”4 Certainly, Lucy’s experience was an exception to the inhumane treatment that most enslaved people endured on plantations in Washington County. Her experiences challenge our conventional understanding of master-slave relationships and sheds light onto the complex nature of these relationships.

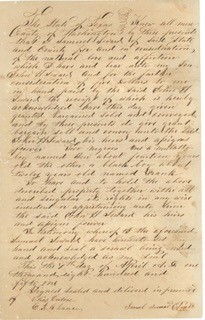

The violence and subjugation that came with slavery were ever present, regardless if some enslaved people did not experience it. Margaret Levingston-Sherrill, an enslaved woman held on the Levingston Plantation, attested to the inhumane treatment and horrors she witnessed. Margaret remembered, “[She] could hear the cries of someone being whipped many times some distance away.”5 Arguably, that dreadful memory imprinted in Margaret’s mind reveals the lasting psychological trauma even those who did not experience violence firsthand took with them into freedom. The life-altering incidents that generated these traumas ranged from being separated from family members, living through sexual assault, and enduring whippings and other forms of violent punishment. Existing bills of sale, like the one on the right, record children being willed and sold within the Seward family, confirming that these traumatic events also took place on this plantation. Lucy and Margaret’s recollections contextualize the experiences of enslaved people on John Seward’s Plantation.

The Seward Plantations on La Bahia Road were home to over a dozen enslaved people. There is limited detailed information about these enslaved people, with only bills of sale, Freedmen’s Bureau labor contracts and a few pictures providing some insight. Several of these bondsmen and women came with the Seward family from Virginia, including “Aunt” Caroline Seward. Caroline was given the family surname, and according to Seward family documents, she worked as a maid on the plantation. Aunt Caroline, presumably had been with Samuel Seward since a very young age. John assumed ownership of Caroline following Samuel’s death. Limited written information exists about her life. However, in the Seward family oral tradition, it is known that Aunt Caroline Seward had seven children by a local white man and ended up staying and working for the Seward family after emancipation. Caroline’s experience provides us with an example of the dilemmas enslaved people faced in determining what freedom would look like to them in the post-Emancipation Era.

Another enslaved person on this plantation whose story is passed down through Seward family oral history is of Uncle Finn. According to oral tradition, Uncle Finn was one of the best stonemasons in Washington County during the 1850s, and even had the freedom to travel around the county to do jobs. Arguably, much of the work he did still stands on the Seward Plantation (See Figures below) and in the antebellum homes and buildings still standing in Independence, Texas.

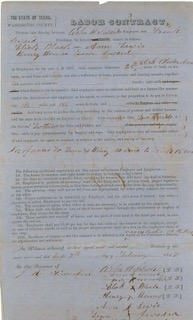

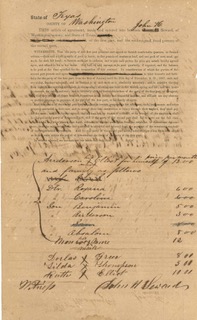

Seward Family records reflect that following the Civil War, several emancipated Black families entered into labor contract with the family. In many instances in Texas, formerly enslaved people often continued to work for their former enslavers. The Reconstruction Era marked a period of significant social upheaval for both Black and white Texans. Arguably, based on the available documents, it appears the Sewards aimed to maintain amicable relations with many of the individuals they formerly owned. (See Images below—Freedmen’s Work Contract, left and Family Payment Ledger, right)

Footnotes

1 James L. Hailey and John Leffler, “Washington County,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed September 27, 2023, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/washington-county. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

2 Slave Narrative of Lucy St. Cyr, Courtesy of © John B. Cade Slave Narratives; Date (1844-1865); Box 1; and Folder Number 187; Archives and Manuscripts Department, John B. Cade Library; Property rights reside with the Archives, Manuscripts and Rare Books Department – John B. Cade Library, Southern University and A&M College. Lucy St. Cyr was about 80 years old when she was interviewed.

3 Slave Narrative of Lucy St. Cyr.

4 Slave Narrative of Lucy St. Cyr.

5 Slave Narrative of Margaret Sherrill-Levingston, John B. Cade Slave Narratives; Date (1852); Box 1; and Folder Number 188; Archives and Manuscripts Department, John B. Cade Library; Property rights reside with the Archives, Manuscripts and Rare Books Department – John B. Cade Library, Southern University and A&M College.