Brazoria County

Locating Personal Experiences in Primary Sources

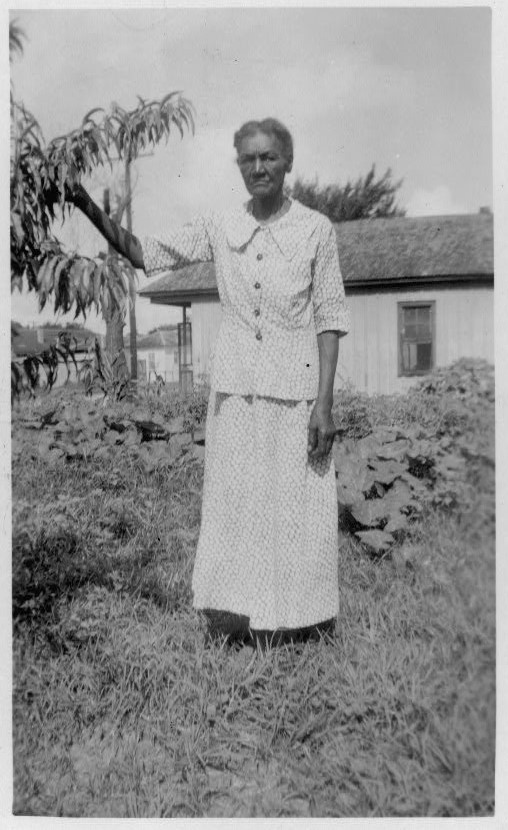

Sarah Mitchell Ford: Slavery and Freedom in Brazoria County, 1854-1945

In Brazoria County, like the rest of the South, enslaved laborers and white slaveholders lived in close proximity. In fact, white landowners included their slaves, in addition to their family members, as part of their plantation household. Within the plantation household, enslaved people created their own family units for community and survival. Families were created by marriage, but families also formed by enslaved people coming together to care for one another regardless of gender, age, or kinship.1 Emancipation in 1865 shattered the plantation household, as newly freed Americans began setting up their own households with family members, neighbors, and friends.2

Sarah Ford was born into slavery on the Patton Plantation in 1854. Sarah’s mother, Jane Mitchell, known as “Lil’ Jane,” was also born on the Patton Plantation. Her father, Mike Mitchell, came to the Patton Plantation from a plantation in Tennessee. Mike was a skilled artisan and tanner who cured animal skins into different types of leather. He understood that his specialized labor was extremely valuable, and he had a reputation for rejecting the violence of slavery.

In her 1936 interview with the Works Progress Administration, Sarah Ford told a story about the strength of her father’s character on the Patton Plantation. The second owner of the plantation, Charles Patton, and the cruel overseer “Uncle Big Jake,” disliked Mike because he was “spirited.”3 What the overseer labeled as “spirited,” Sarah Ford labeled as a man who understood who he was, what he contributed to the community, and the wealth his labor provided for the Patton family. Mike defined himself beyond the bounds of slavery, as a husband and father. He was more than a tanner and understood that his skilled labor meant he could reject some of the violence and oppression that gave the Peculiar Institution some of its corporeal power.

Sarah recalled an incident when “Uncle Jake” threatened her father with physical punishment after they had a disagreement. Mike responded by running away. He stayed away for an entire year. When he first disappeared, Charles Patton sent a slave catcher with dogs to catch him. Mike avoided capture, and the slave catcher returned empty handed. Sarah also recalled that when her father ran away he always found work. Mike realized that his skills as a tanner could keep him and his family fed and clothed whether on the plantation or off. For some time, Mike resided with a German family where he tanned animal hides and made money to support his family. Mike would secretly return to the plantation to leave food or store-bought dresses for Sarah and her mother. Delivering these gifts came at a great personal cost, but Mike was committed to supporting his family. When Uncle Jake learned about the clothes, he threatened to whip Sarah’s mother, Lil’ Jane. Mike learned of the threat and returned to the plantation in time to protect his wife from Uncle Jake’s whip, and took on the punishment himself. Mike was whipped and spent three additional days chained in the stockhouse without food or water.4

As members of the plantation household, both Charles Patton and Uncle Jake were well known among the slaves on the Patton Plantation. When describing her enslaver, Sarah stated, “Massa Charles…was ‘bout de same all white folks that owned slaves, some good some bad.” What might be read as ambivalence about Patton in this description might actually point to the fact that Sarah understood that while Patton himself did not enact direct forms of violence, he allowed the overseer Uncle Jake to work the slaves from early morning until night.

Uncle Jake was known for brutally disciplining enslaved laborers on the plantation. Sarah details the punishment he delivered to any runaway that was caught absconding. The enslaved person, man or woman, was tied face down with their hands and feet tethered tightly to four wooden posts driven into the ground. After the person was secured, Uncle Jake enacted his own unique brand of cruelty. He used an implement he named the slut—a metal bar with small holes drilled through it—that he filled with tallow, a type of animal fat. He then placed the slut on a fire. Once the iron was red hot and the tallow bubbled, Uncle Jake poured the searing liquid on the enslaved person’s back. While their backs burned from the scalding tallow, he used a bullwhip to whip them. He did not restrict his blows; he beat them across the entire backside of their restrained bodies. After this sadistic display of violence couched as punishment for desiring freedom, fairness, or family, the enslaved person was locked.

The trauma from this type of extreme violence was not restricted to those who received the lash. Those who witnessed it were also traumatized. The fact that Sarah recalled the details so vividly eight decades after emancipation demonstrates that an entire family and community also felt the suffering and experienced lasting impact upon the now free women and men of the Patton Plantation.

Sarah and her family stayed on the Patton Plantation through the end of the Civil War. She describes the day Union soldiers declared their freedom as the “bright light.” Even though Charles Patton promised to pay wages to the formerly enslaved people on the plantation, Sarah’s family did not stay. Instead, her father, Mike, left and returned with a borrowed wagon and mules. He took his family to East Columbia, Texas, just across the Brazos River, where the Mitchell family built a cabin and a corn crib and began to build their new lives.

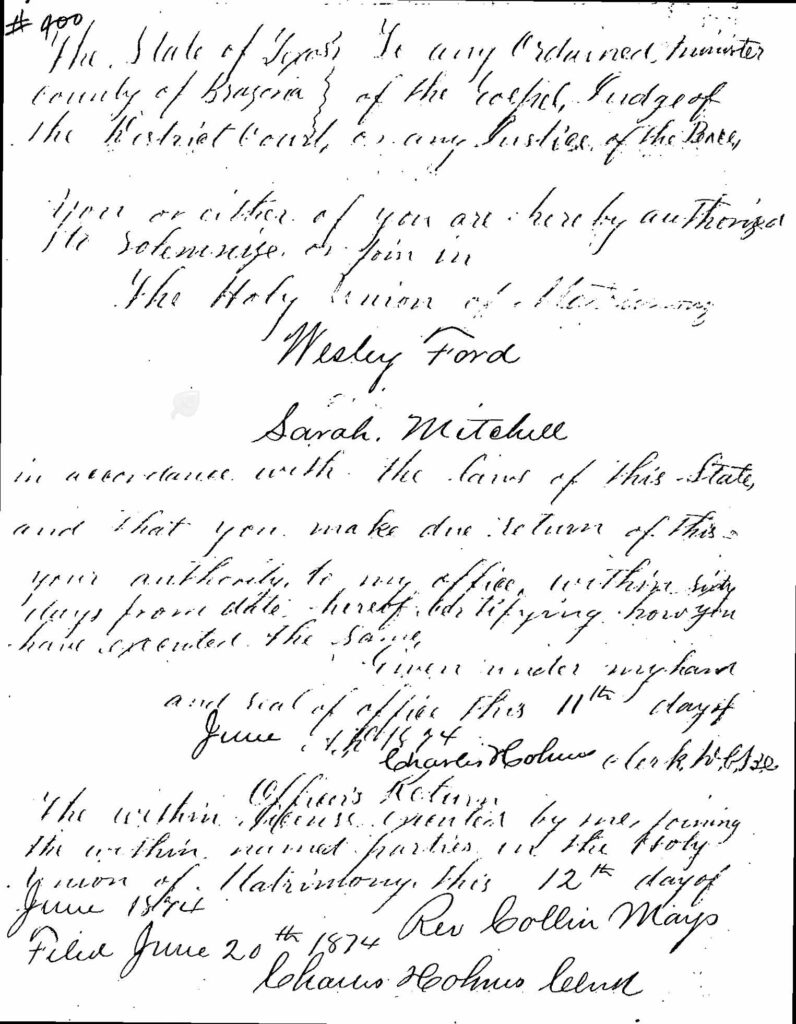

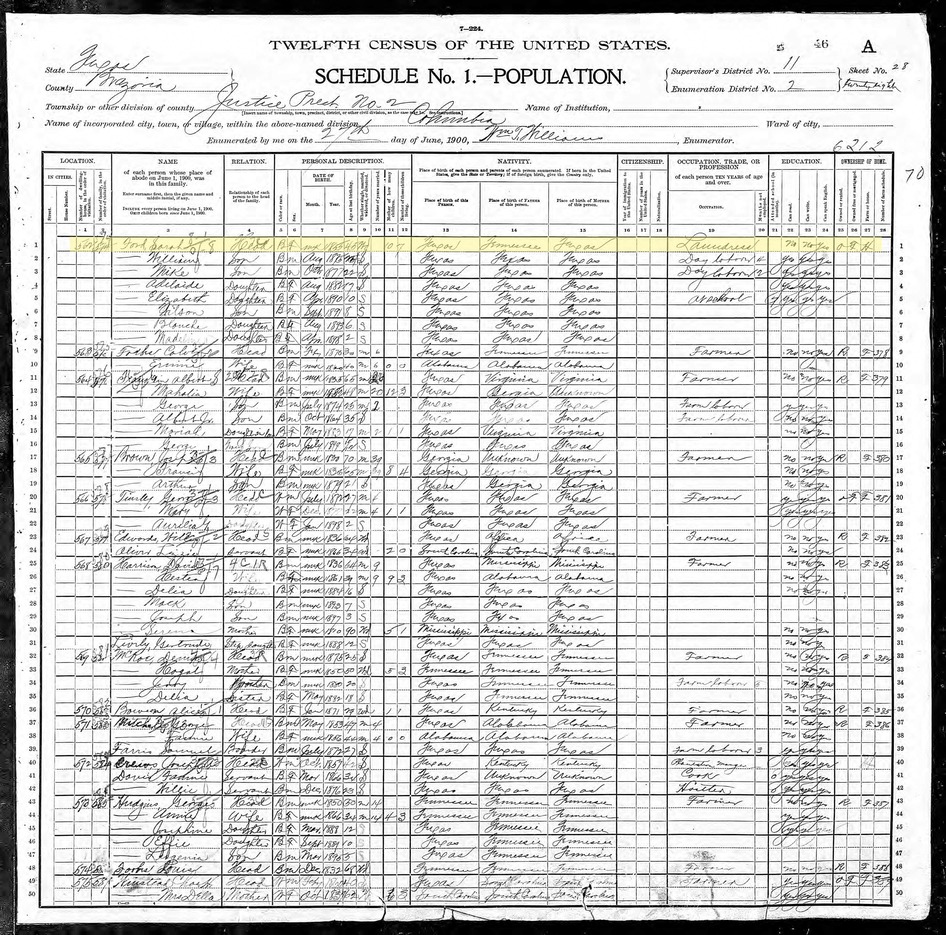

Newly free Black farmers relied heavily on their family units to complete household tasks like taking care of livestock and working the land.5 By working together, family members provided support to survive and together, they developed thriving communities. Sarah lived with her parents until 1874, when she married Wesley Ford in Brazoria County. The couple lived close to Sarah’s parents, and by 1886 they had purchased their own plot of land in Columbia County. Sarah and Wesley had seven children before Wesley died sometime between 1897 and 1900. The 1900 census lists Sarah as a widow, homeowner, and a laundress living with her children William, Mike, Adelaide, Elizabeth, Wilson, Blanche, and Madeline.

By 1910, Sarah had moved to Houston’s Third Ward where she continued to work as a laundress, and later helped raise two of her grandchildren. Sarah Mitchell Ford died in Houston on January 27, 1945, and was buried in West Columbia, TX. She was survived by four children and several grandchildren.

Footnotes

1 Nancy Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms: Race, Rights, and the Politics of Household in the Delta, 1861-1875. (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 5.

2 Ibid., 19.

3 “Interview with Sarah Ford” (Washington D. C., 1940), Library of Congress, 43.

4 Ibid., 44-5.

5 Dylan C. Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 166-168.