Brazoria County

Locating Personal Experiences in Primary Sources

Rachel Bartlett: Power Dynamics on Plantations, 1834-1880

The Patton Plantation sits in the heart of Brazoria County near the Brazos River.1 In 1834, Columbus “Kit” Patton purchased 4,428 acres of land that was previously the Varner Plantation. Over the next decade, Patton significantly increased his wealth–amassing over 17,000 acres of land, 1,500 head of cattle, forty-nine workhorses, and he enslaved sixty-five people.

The Patton family ran the plantation just like a factory, and the enslaved people on the Patton Plantation did more than work the fields. Specialized labor on the plantation included a tanner and a shoemaker. There was also a plantation cook named Judy, who also performed the duties of healer and a man called Law, who was a preacher. Law performed his teaching in the plantation arbor, a location on the farm full of shade from trees. However, his days of preaching were cut short when one day, Law decided to teach that God made everyone equal, saying, “De Lawd make everyone to come in unity and on de level, both white and black.”2 After learning of this preaching on racial equality, Charles Patton immediately demoted Law, putting him back to work in the fields weeding and cutting sugarcane.

Columbus Patton never married and had no children. However, he lived with an enslaved woman named Rachel. In a 1936 interview with the Works Progress Administration, Sarah Ford described Rachel as “an African woman from Kentucky” and remembered that the enslaved people on the Patton Plantation called her “Mistress.” This suggests that Rachel occupied a place of privilege and influence within Patton’s household. In this position, she performed household duties ordinarily reserved for the plantation mistress–managing household tasks and the people forced to work in this space.

Not much is known about Rachel Bartlett. Her voice is absent from the documents and records historians rely on to excavate the past. Her thoughts and concerns were not recorded for posterity, and no photographs of her exist. Despite this, the extant records indicate she wielded considerable influence on the Patton plantation. Rachel’s elevated position created dissension within the Patton family. Charles Patton argued that Rachel held undue influence over Columbus. The Patton family used this allegation to take control away from Columbus and then had him committed to an asylum in South Carolina. In 1854, Charles Patton took over management of the plantation and immediately forced Rachel out of the house and into the fields.

John Adriance, the executor of Columbus Patton’s estate, produced a will Columbus had written three years prior to his death in 1856. Although he did not leave her the one thing that likely mattered to her the most—her freedom—he made significant provisions for her. His will decreed that Rachel was to receive $100 per year and have her own residence on the Patton Plantation. In addition, perhaps seeking to provide some kind of stability for Rachel, he decreed that she was not to be hired out to work outside of the Patton Plantation. Probate records document that Rachel used the payment from Adriance to purchase beads, fringe, cloth, sugar, bar soap, and dresses for herself and other enslaved women. Despite the prohibition in Columbus’s will, in 1858 and 1859, she was hired out for seventy-five dollars a year, which largely paid for her stipend. In 1860 as Texas braced for war, John Adriance demonstrated remarkable forethought and sent Rachel to live in the large free Black community in Cincinnati where Rachel took the name Bartlett and continued to receive the yearly income bequeathed to her.3

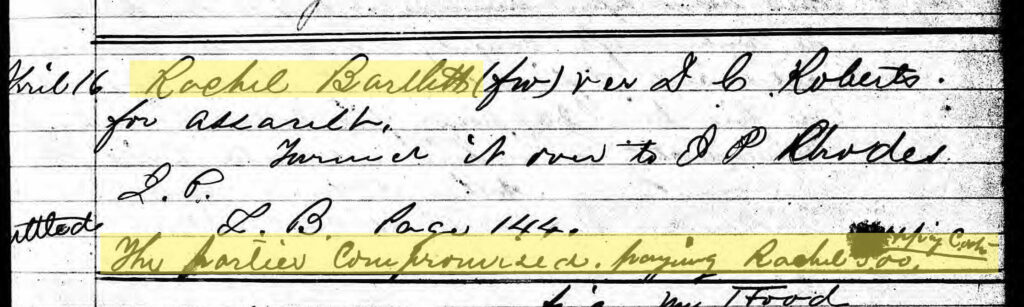

Surprisingly, Rachel came back to Brazoria County in 1868. Though the Civil War was over, many Texas planters acted as though slavery had not ended. Black Texans lived under a constant threat of violence, and in an attempt to seek justice, some reported the crime and harm done to them to the Freedmen’s Bureau.4 Upon her return, Rachel received her annual allowance through purchase accounts at local stores that were charged to Columbus Patton’s estate. Then, on April 16, 1868, Rachel was assaulted by David C. Roberts, a Confederate veteran. She took it upon herself to report this act to the Freedmen’s Bureau office in West Columbia, TX. The Bureau corresponded with all parties, and Rachel received a $500 settlement.

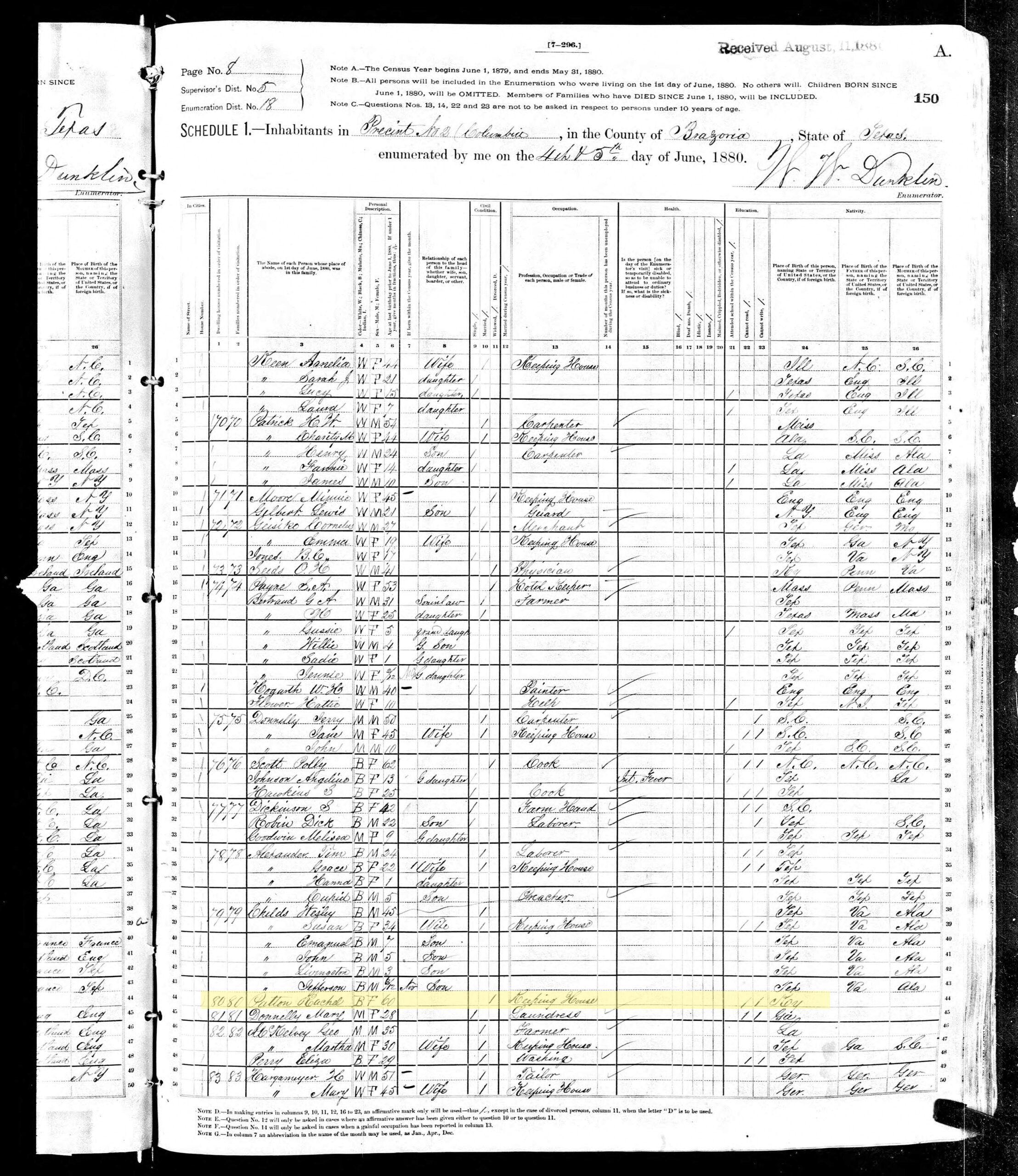

In the year following Rachel’s attack, the Patton Plantation was sold. Rachel is last seen in the 1880 federal census, identified as Rachel Patton, a sixty-year-old widow from Kentucky who was described as keeping house. Although we do not know why Rachel chose to change her name from Bartlett to Patton in her later years, perhaps this decision was an attempt to claim a part of her identity that was important to her.

Footnotes

1 Today, it is also known as the Varner Hogg Plantation and Ranch.

2 “Interview with Sarah Ford” (Washington D. C., 1940), Library of Congress, 45.

3 John Lundberg, “Patton, Rachel,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/patton-rachel.

4 McDaniel, W. Caleb. Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 171.