Brazoria County

Locating Personal Experiences in Primary Sources

The Freedmen’s Bureau in Brazoria County, 1865-1867

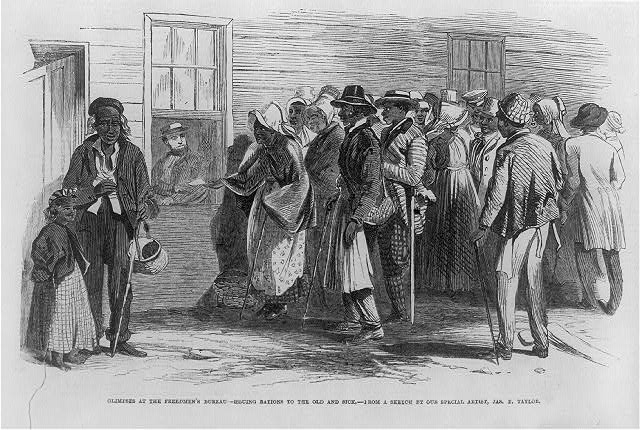

In 1865, the United States Army War Department created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. After the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau oversaw relief efforts and social services to formerly enslaved and poor white people. In addition to providing medical care, food, clothing, educational and employment opportunities, the Freedmen’s Bureau also helped the formerly enslaved find relatives, secure marriage licenses, and register to vote.

The Freedmen’s Bureau operated in Texas from September 1865 until July 1870. Bureau offices were often understaffed and under-resourced to address the overwhelming need. By May 1866, the Freedmen’s Bureau had 30 branch offices across Texas, including one in Brazoria County.

The Case

In 1867, Manual Hunt, Gus Bess, Edward Bess, Payton Munroe, and Ben Lee filed a claim with the Freedmen’s Bureau against farmer and former enslaver Stephen P. Winston. The five men claimed that Winston violated the terms of their labor contract and threatened them. Winston acted on behalf of his mother, who held legal ownership of the land he managed.

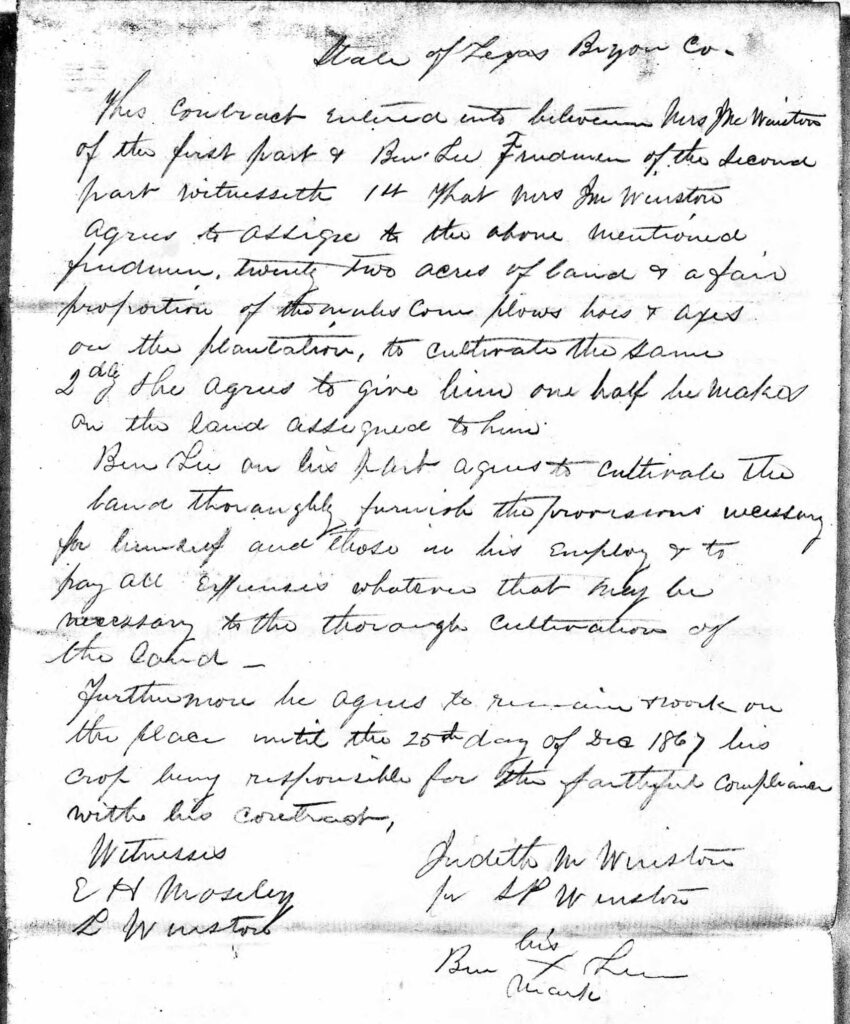

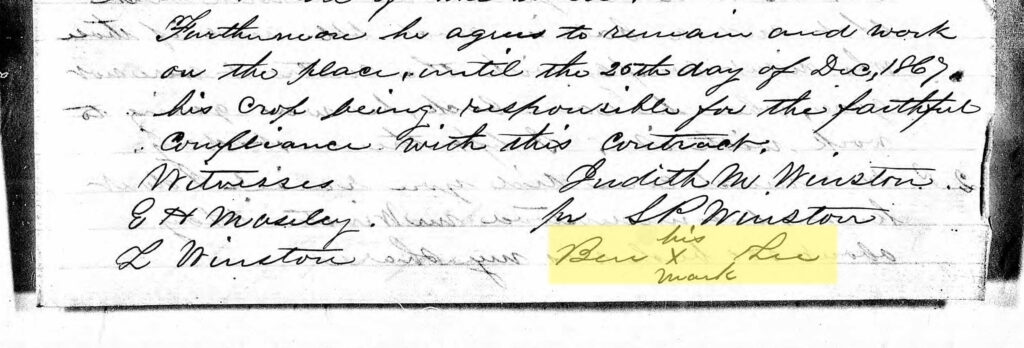

Like many newly freed people after the Civil War, these men entered into labor contracts necessary to work in Texas. Labor agreements between white plantation owners and Black laborers offered leased housing, land, and either a percentage of raised crops or a portion of their sale in return for working the land. However, these arrangements still exploited Black workers because they did not allow Black farmers to earn enough to make a living. Instead, these labor agreements ensured the land owner’s financial success and protected their best interests. These kinds of abusive working conditions were only reinforced by restrictive laws called Black Codes that the Texas legislature enacted in 1866. Because most formerly enslaved people could not read or write, white landowners read the contracts to them aloud. This created an opportunity for white landowners to further exploit and manipulate the people who worked their land. After they were read, Black laborers had to sign the agreement with an X mark.

The contracts Manual Hunt, Gus Bess, Edward Bess, Payton Munroe, and Ben Lee signed with Stephen P. Winston provided each of them with twenty-two acres of land along Cedar Lake in Brazoria County to cultivate. Winston also provided mules, plows, corn, axes, and supplies needed. Winston required that each man work until December 25 of that year, and in return, each man would receive one half of what he raised on the land assigned to him.

Manual Hunt, Gus Bess, Edward Bess, Payton Munroe, and Ben Lee asserted that they were expected to work until December 25, 1867. Winston accused them of violating their work contract, threatened them with violence, demanded they leave the farm, and withheld their earned share of corn and livestock. Freedmen’s Bureau records

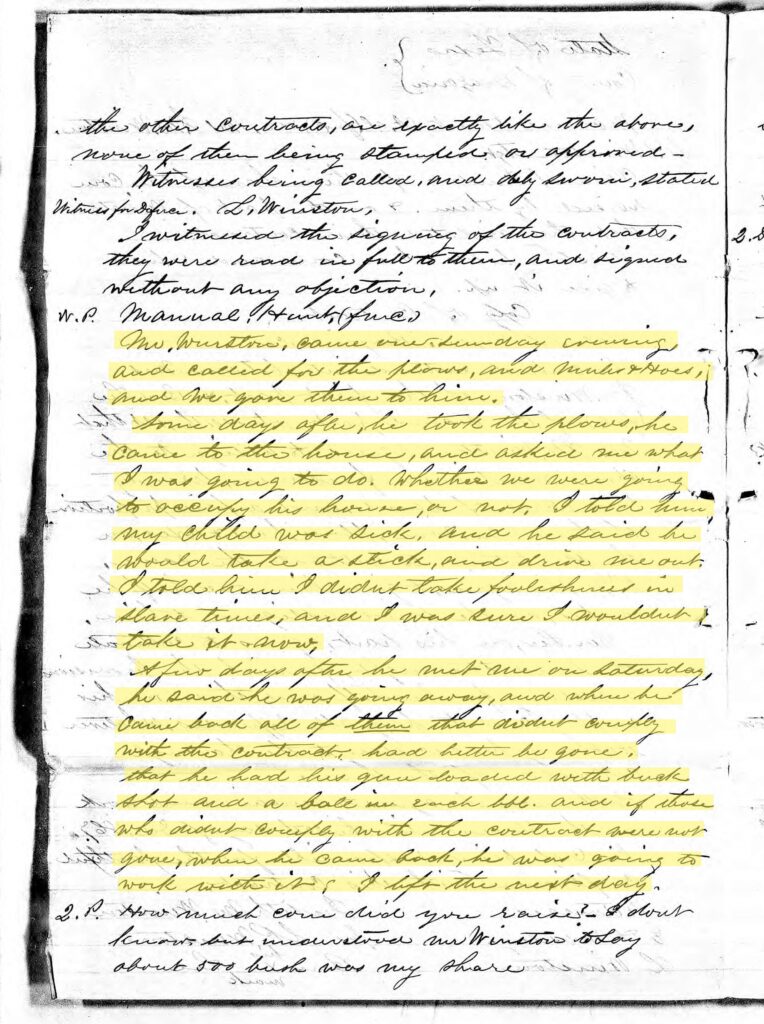

Manual Hunt stated:

Mr. Winston came one Sunday evening and called for the plows and mules & hoes and we gave them to him. Some days after, he took the plows, he came to the house, and asked me what I was going to do. Whether we were going to occupy his house or not. I told him my child was sick and he said he would take a stick and drive me out. I told him I didn’t take foolishness in slave times, and I was sure I wouldn’t take it now.

A few days after he met me on Saturday, he said he was going away, and when he came back all of them that didn’t comply with the contract had better be gone. That he had his gun loaded with buck shots and a bale in each [bbl.] and if those who didn’t comply with the contract were not gone when he came back, he was going to work with it. I left the next day.

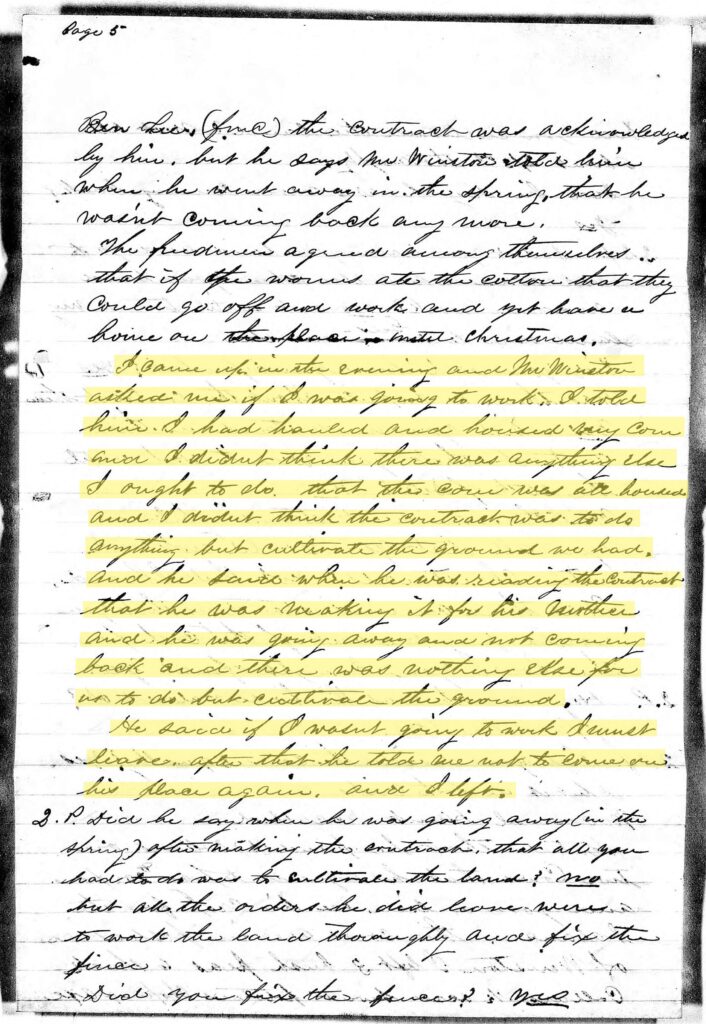

Ben Lee testified:

I came up in the evening and Mr. Winston asked me if I was going to work. I told him I had hauled and housed my corn and I didn’t think there was anything else I ought to do. That the corn was still housed and I didn’t think the contract was to do anything but cultivate the ground we had and he said when he was reading the contract that he was making it for his mother and he was going away and not coming back and there was nothing else for us to do but cultivate the ground.

He said if I wasn’t going to work I must leave. After that he told me not to come on his place again. And I left.

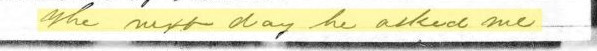

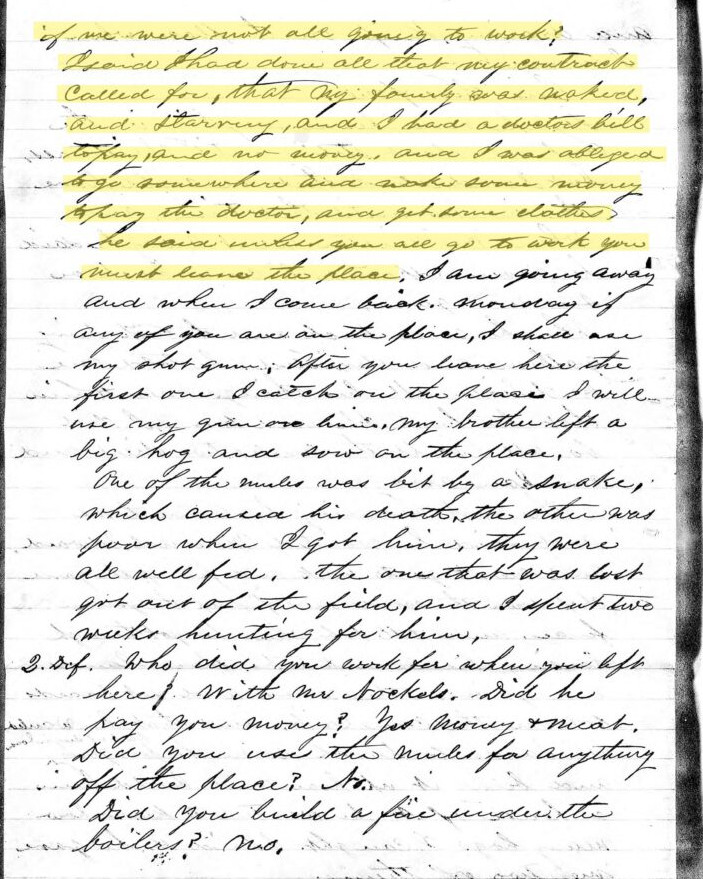

Gus Bess said:

The next day he asked me if we were not all going to work? I said I had done all that my contract called for, that my family was naked and starving, and I had a doctors bill to pay, and no money. And I was allowed to go somewhere and make some money to pay the doctor, and get some clothes. He said unless you all go to work you must leave the place.

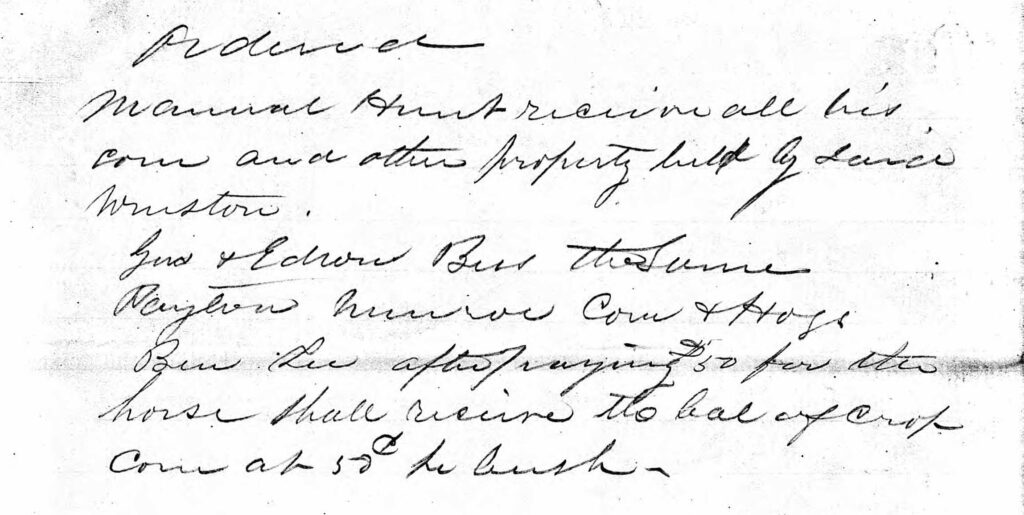

During the proceedings, both Freedmen’s Bureau commissioners and Stephen P. Winston interviewed the men and other witnesses about their understanding of the contract and the actions taken by Winston. At the end of the case, the Freedmen’s Bureau sided with the men and ordered:

Manual Hunt receive all his corn and other property held by said Winston.

Gus and Edward Bess the same

Payton Munroe corn & hogs

Ben Lee after paying $50 for the horse shall receive the bal of crop corn at 50 cents per bush

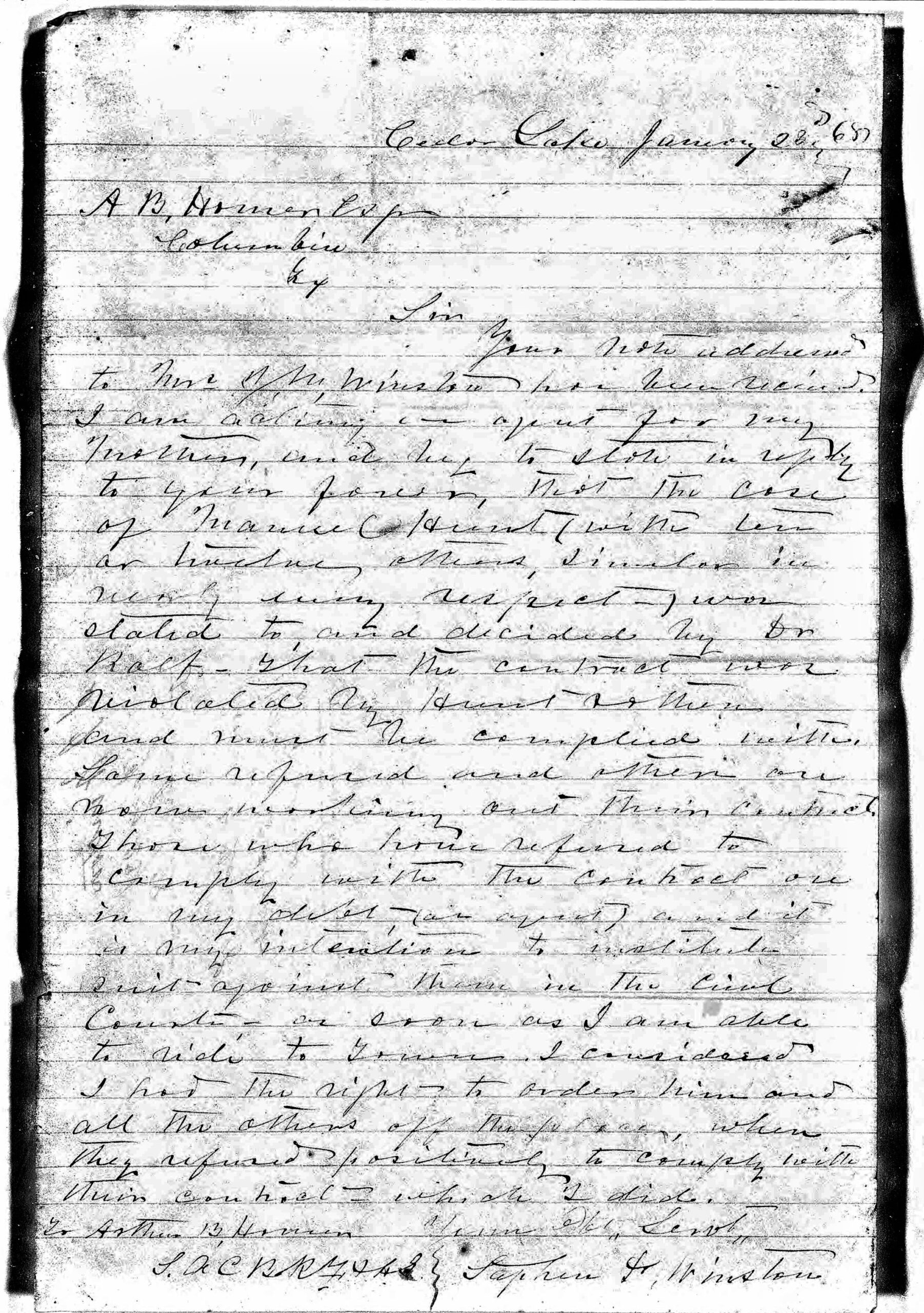

Following the case, on January 28, 1868, Winston wrote to A.B. Horman, Esq. stating that he intended to initiate a suit against Manual Hunt and others who he claimed were in violation of their contracts. It’s unknown if Winston pursued this case. However, nearly three years later Winston filed for bankruptcy which was finalized on May 30, 1871.

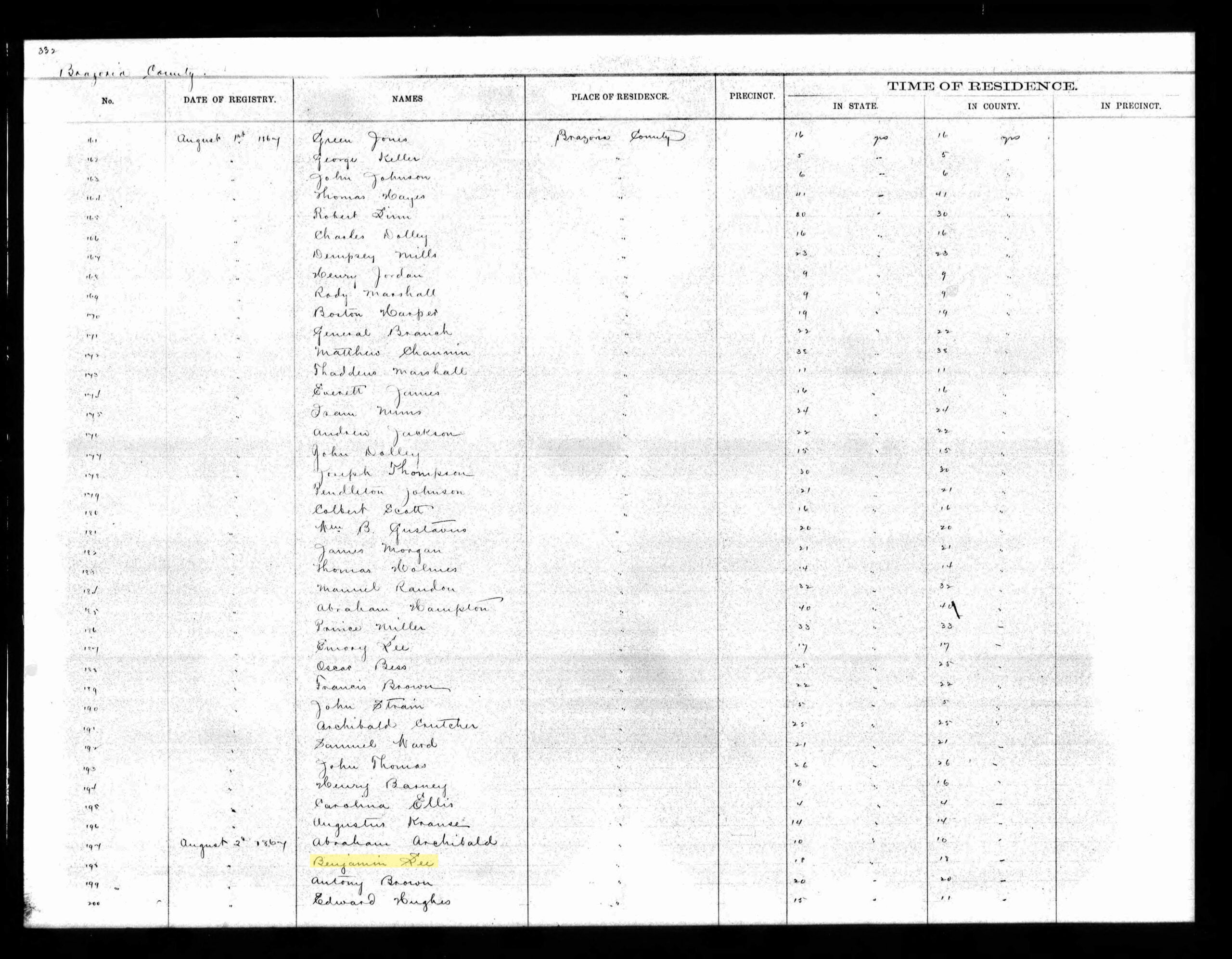

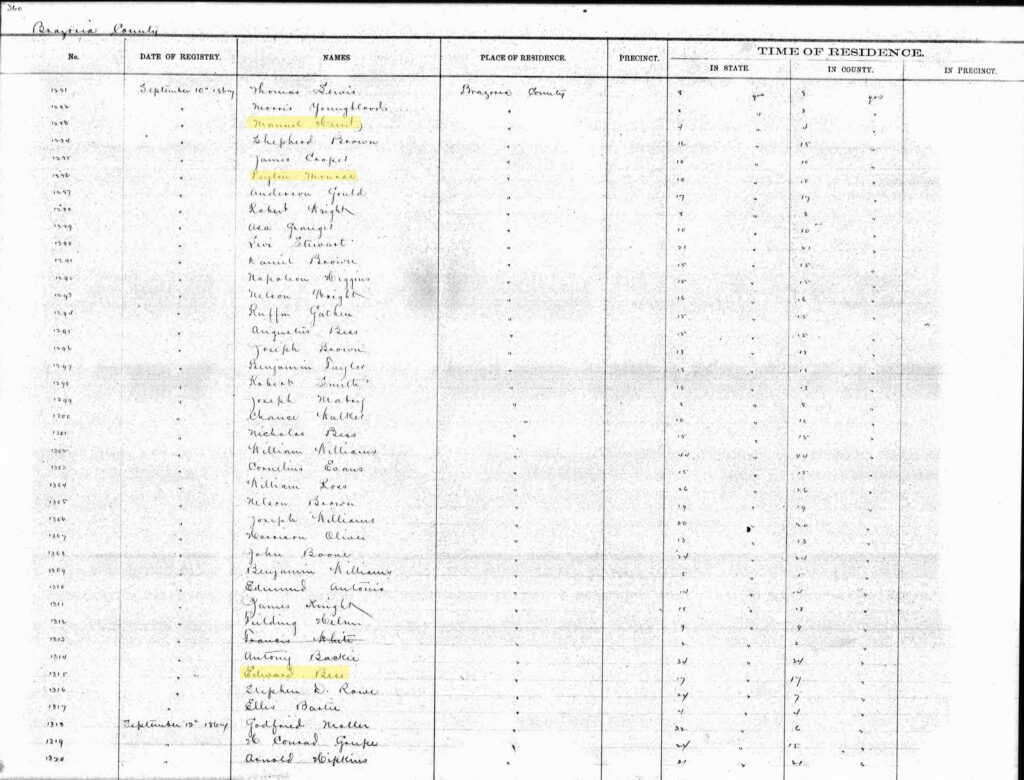

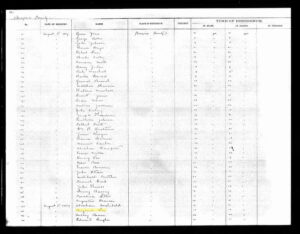

In 1867, the same year they filed their claim with the Freedmen’s Bureau, Manual Hunt, Edward Bess, and Payton Munroe registered to vote in Brazoria County. While we do not know much about the relationship between these men, it is clear that they knew each other well. Perhaps their experience with the Freedmen’s Bureau case empowered them to act together once again and register to vote soon after emancipation.

The Freedmen

Manual Hunt

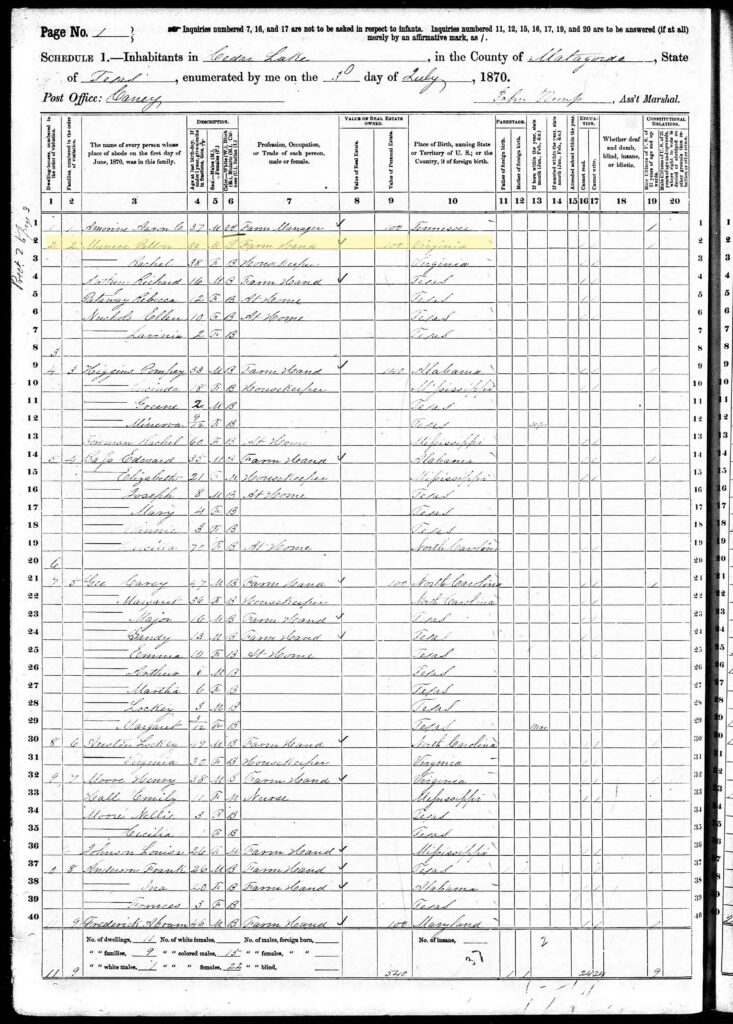

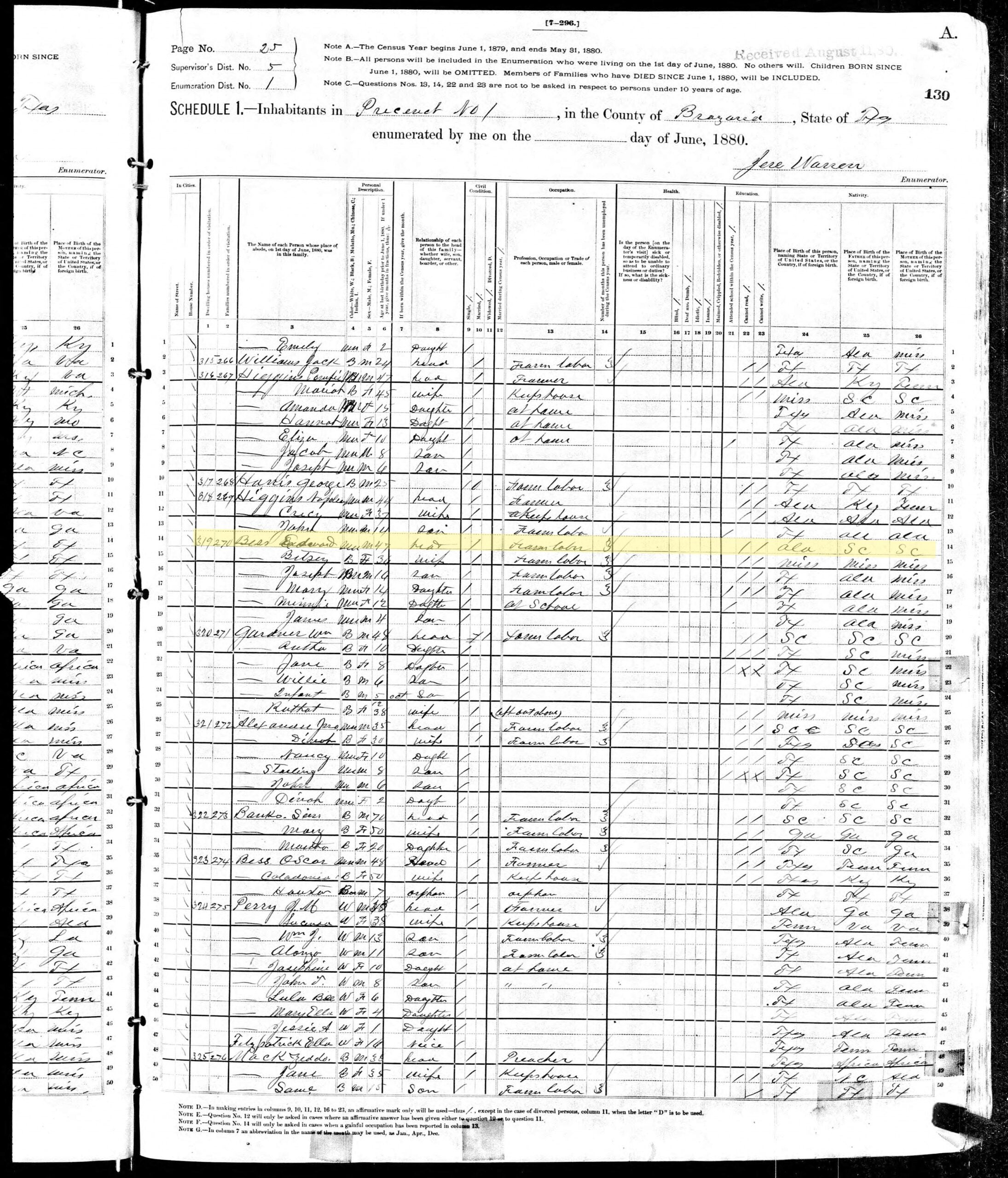

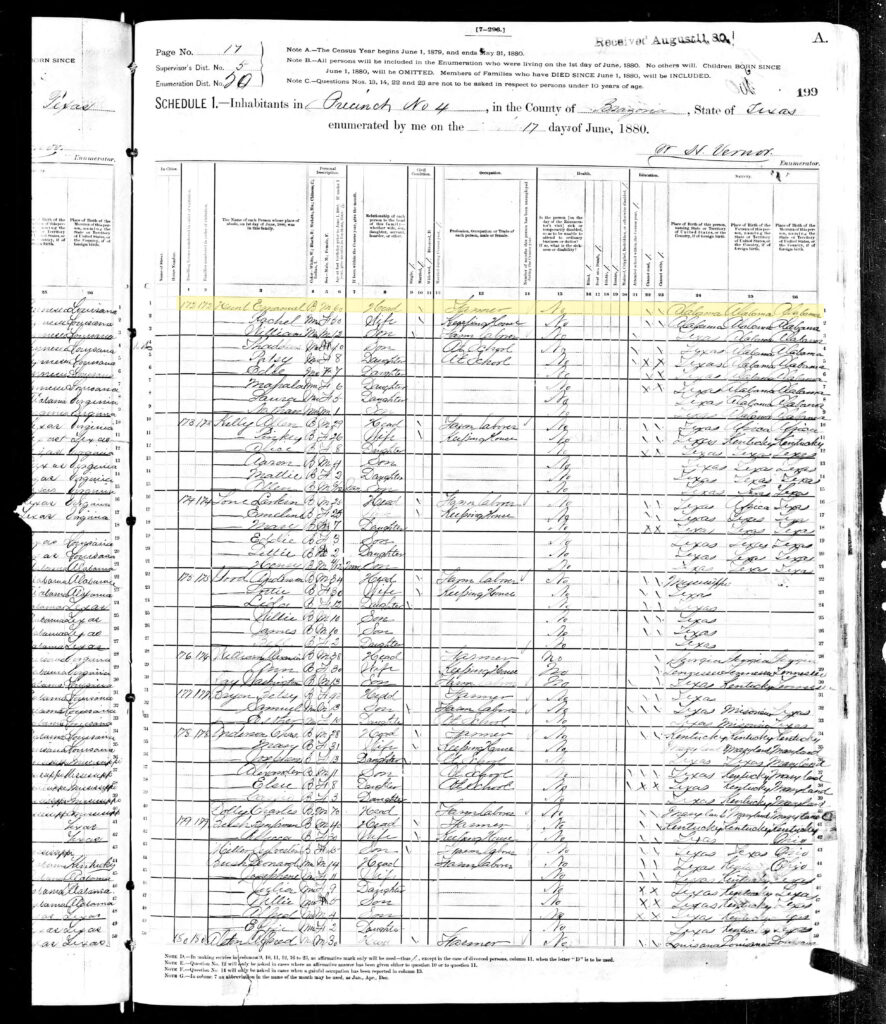

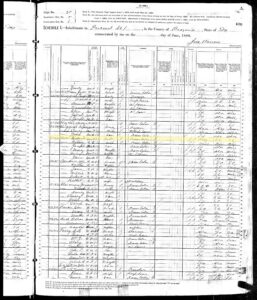

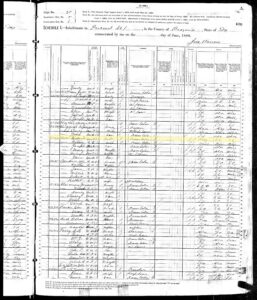

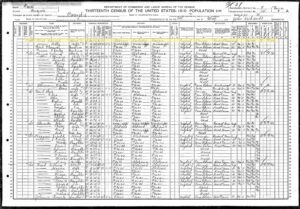

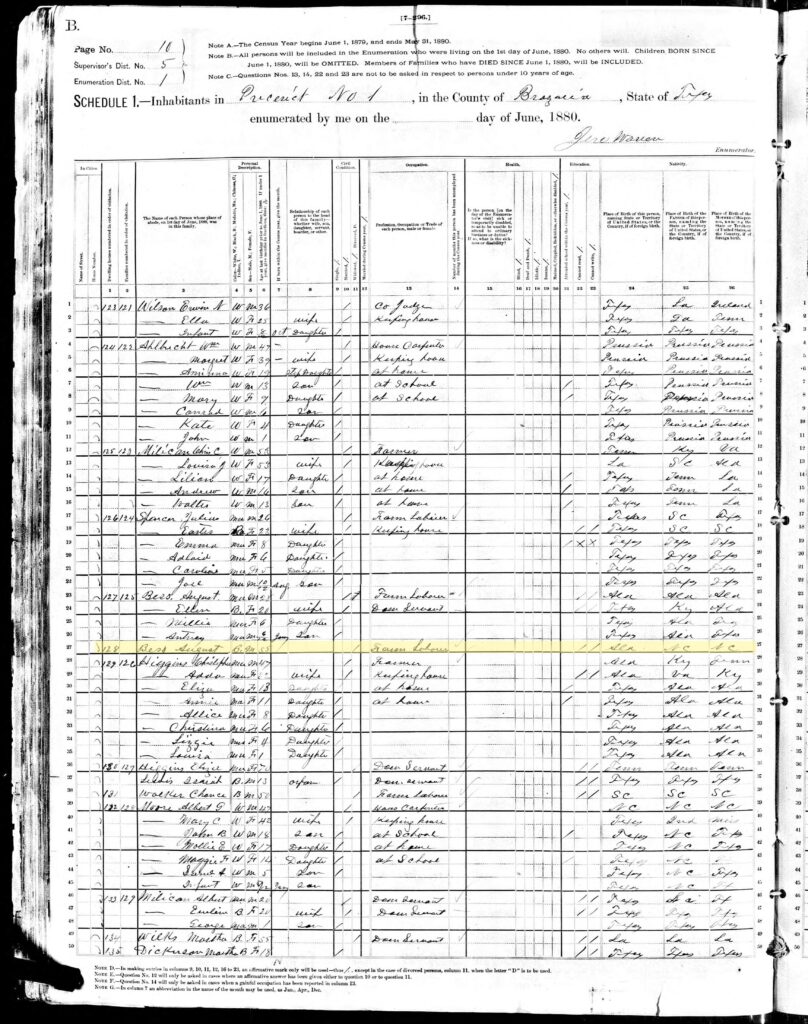

Manual Hunt was born around 1820 in Alabama. He was likely forced to relocate when the white, landowning Winston family of Tuscumbia, Alabama, chose to move to Texas around 1851. On September 10, 1867, Hunt registered to vote in Brazoria County with Edward Bess and Peyton Munroe. By 1880, Emanuel Hunt was living with his wife Rachel and their seven children William, Thaddeus, Patsy, Edie, Mahala, Laura, and Nathan in Brazoria County, Texas.

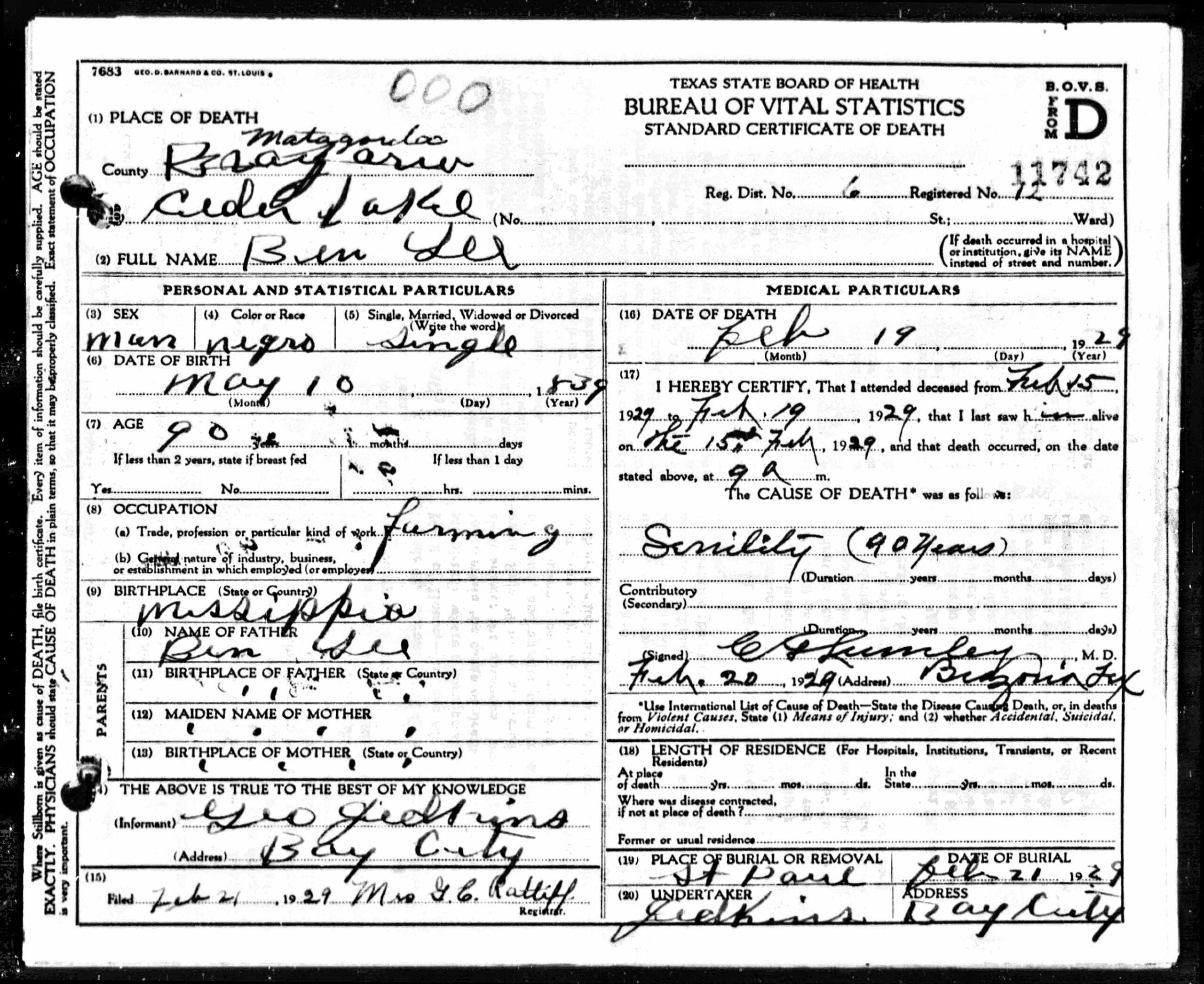

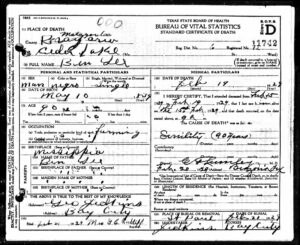

Benjamin Lee

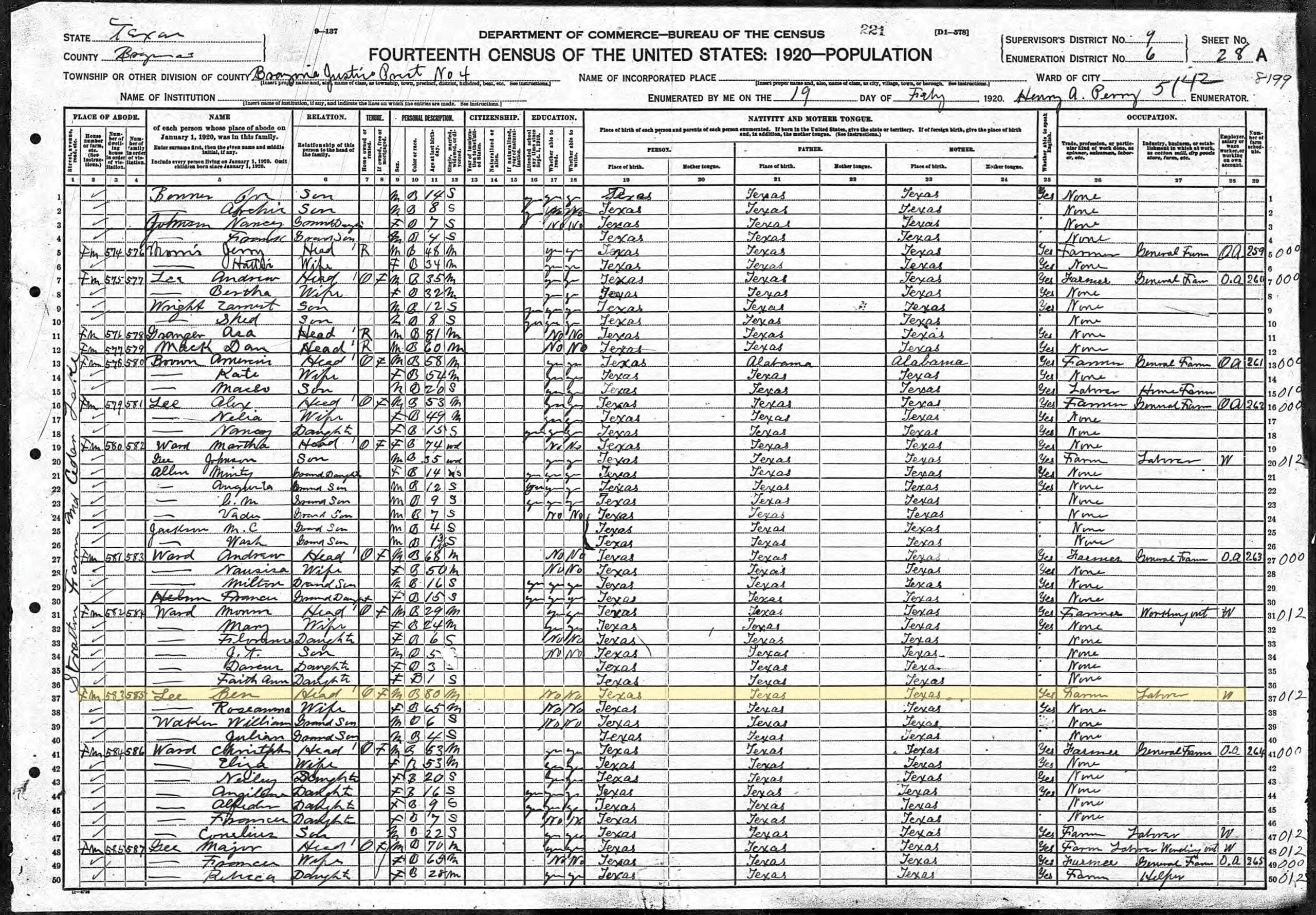

Benjamin Lee was born around 1838 in Mississippi. Ben Lee registered to vote in Texas soon after emancipation on August 2, 1867. In 1880, he lived with his wife Amanda and their children Alexander, Creacy, Louiza, Adaline, Josephine, and Major in Brazoria County. Ben Lee passed away at 90 years old on February 19, 1929 in Cedar Lake, Matagorda, Texas.

Ed Bess

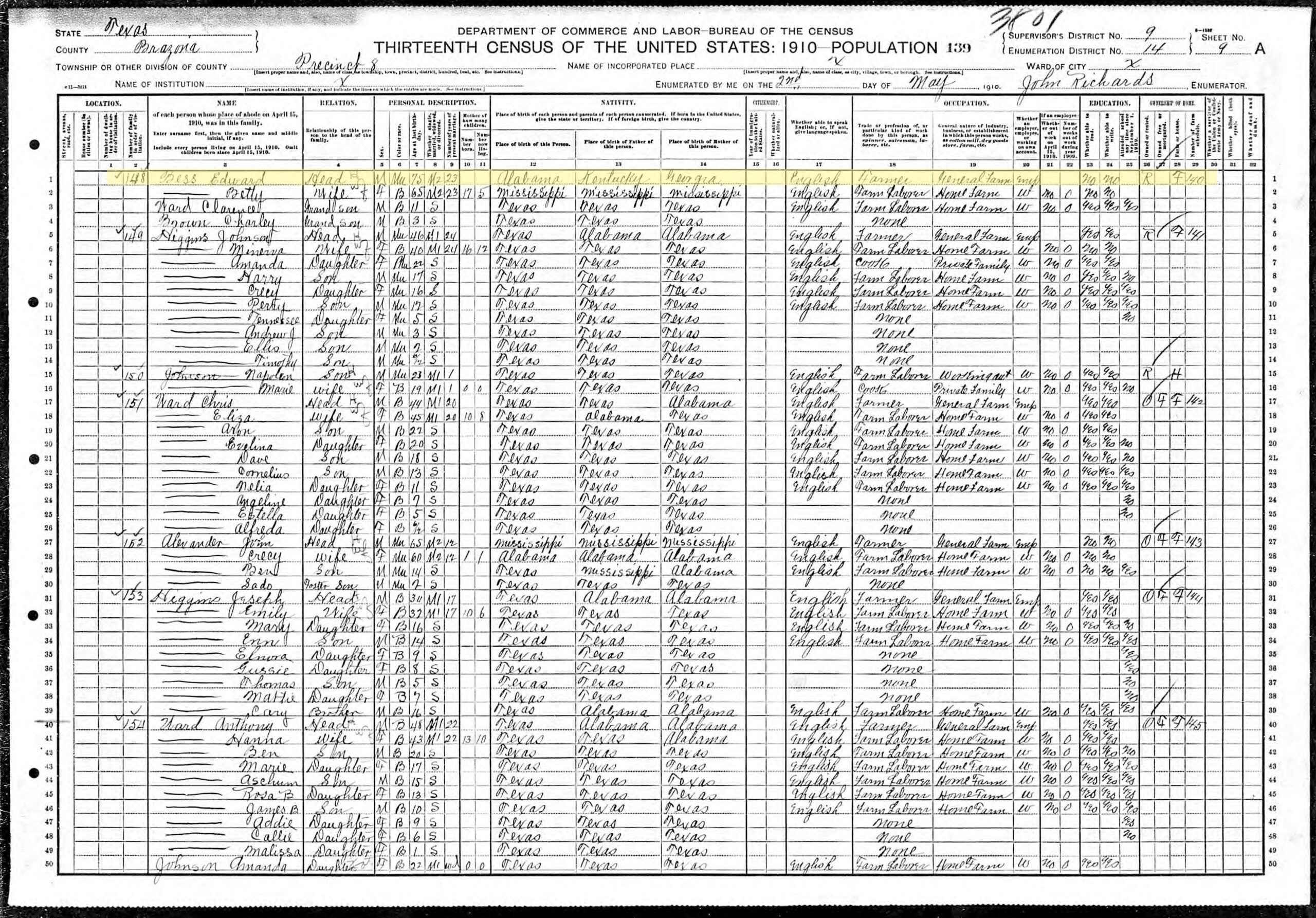

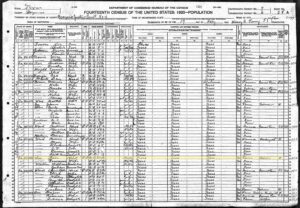

Ed Bess was born in 1835 in Alabama. A mulatto, he likely came to Texas with the Winston family. Census records indicate his parents were born in South Carolina, Kentucky, or Georgia. Shortly after emancipation, on September 10, 1867, Edward Bess registered to vote in Brazoria County. By 1880, Edward lived with his wife Betsey/Betty and their children Joseph, Mary, Minnie, and James. In 1910, at age 75, Ed Bess and his wife lived with their two grandsons, Clarence Ward and Charley Brown.

Gus Bess

Gus Bess was born in Alabama around 1825, and was likely forced to relocate when the white, landowning Winston family of Tuscumbia, Alabama, chose to move to Texas around 1851. Records detailing his life are very limited. In 1880, census records show a man named August Bess living alone in Brazoria County. He lived next door to a younger man, also named August Bess, likely the elder Bess’s son. The younger August Bess, aged 28, lived with his wife Ellen and their two children, Millie and Aubrey.

Payton [Peyton/Patton] Munroe

Payton [Peyton/Patton] Munroe Records about Payton Munroe are limited. In 1858, Brazoria County Deed Records show a 28-year-old man named Peyton is listed among Stephen P. Winston’s property, which suggests Payton Munroe may have been enslaved by Winston, and then worked for him after emancipation. If this is the same Payton, he would have been around 37-years-old at the time of the Freedmen’s Bureau case. Alternatively, the 1870 census indicates there was a Patton Munroe born in Virginia around 1840 and living at Cedar Lake, Matagorda, Texas. If this is the same person, Patton would have been around 27-years-old at the time of the Freedmen’s Bureau case.