Brazoria County

Locating Personal Experiences in Primary Sources

Stephen P. Winston and Cedar Lake Plantation, 1852-1881

Stephen Parks Winston was born sometime between 1825-1828 in Franklin, Alabama, to William Henry Winston and Judith McGraw (Jones) Winston. He had at least two siblings, Anderson and Patsy. In February 1848, he married Ann C. Winston in Greene, Alabama, and they had four children together: Mary, Sarah, Ann, and John.

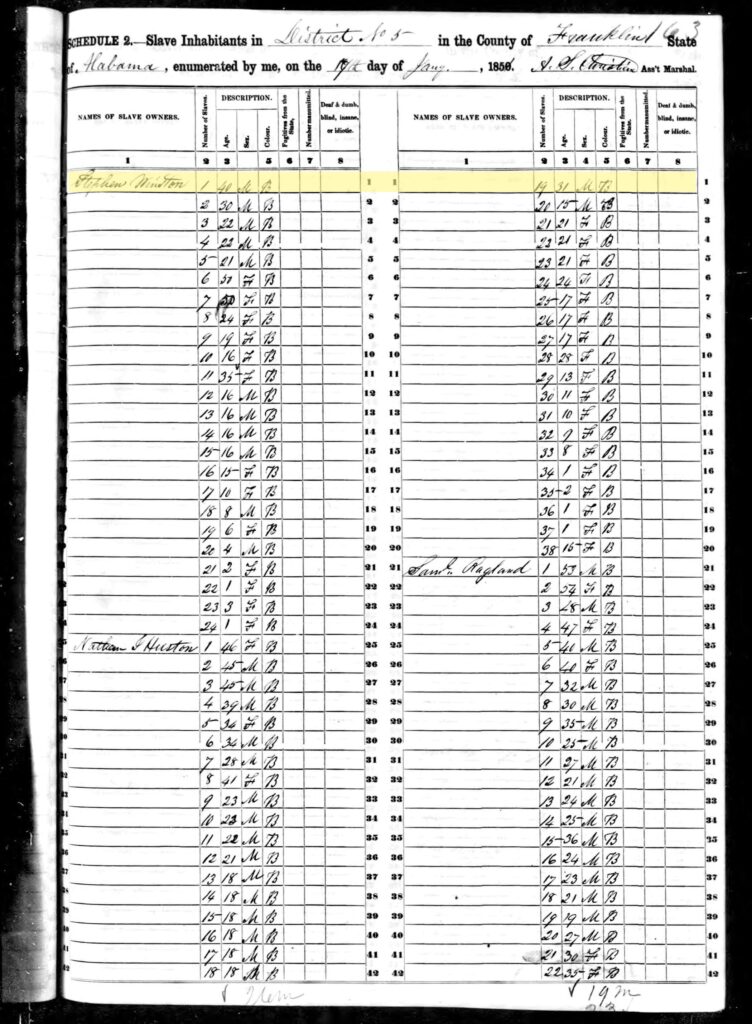

In Alabama, Winston worked as a planter. He owned his own land and he also owned slaves.

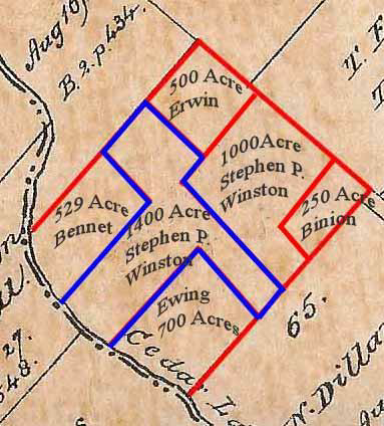

In 1852, with his father’s financial support, Winston purchased two tracks of land along Cedar Lake in Brazoria County. This area would become his new home.

By 1853, Winston enslaved 25 people who cultivated and produced sugar on his plantation. Not only did Winston’s father provide the financial support necessary to purchase the land, but he also retained a vested interest in the Cedar Lake plantation’s success. He enslaved 61 people who were forced to labor there. Amanda and Payton were likely two of these 61 people.

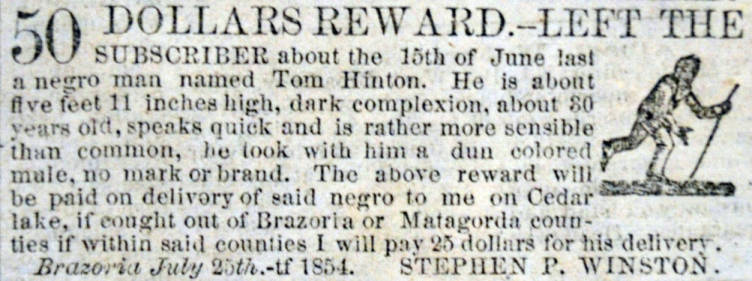

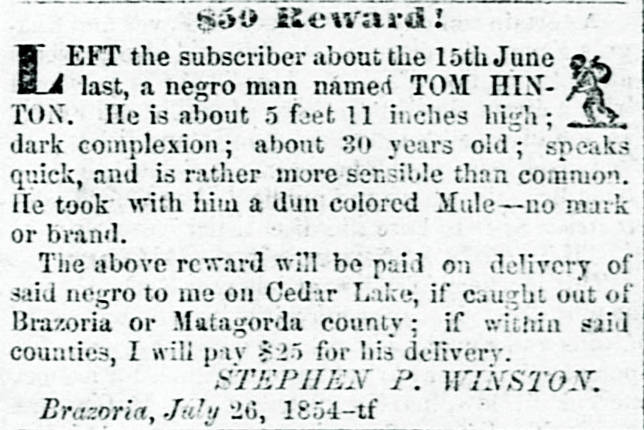

Cedar Lake plantation relied on the labor of enslaved people. Resisting the hard labor and subjugation, records show that at least one man ran away from the plantation. In July 1854, Winston’s efforts to reclaim a runaway slave named Tom Hinton were revealed through the Texas Advertiser. In his ad, Winston offered a $25 reward if Tom was captured in either Brazoria or Matagorda Counties, or $50 if he was captured beyond. The ads were published a few weeks apart–the first appeared on August 1 and the second on August 23. The outcome of this search remains unknown.

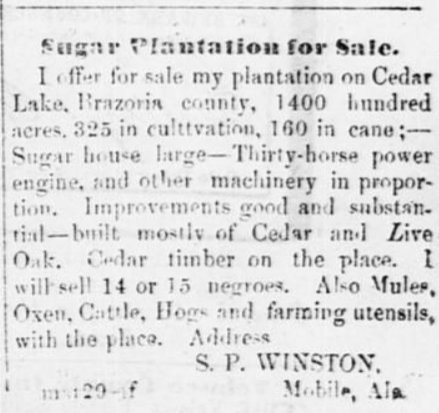

In 1857, Stephen’s father passed away, thrusting him into the role of managing the Brazoria plantation and all of its debt. By 1859, Winston put the plantation property up for sale, including “14 or 15 negroes,” and returned to Alabama.

While he was away, other members of the Winston family settled along Cedar Lake likely managed the property and the enslaved people working it. However, in 1860 things changed, and Winston took complete financial control of the plantation that was still struggling financially. That same year, his wife Anne died. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Winston joined the Confederate Army. After serving the Confederacy, Winston returned to Texas and married Sallie Winston in 1863.

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved people chose to remain where they were–for every person who left the plantation, hundreds remained behind.1 This was especially true in Texas, where traveling roads after the war was dangerous for Black people. It was known that if you left, you could encounter violent gangs of white gunmen, many of them war veterans, who would harm you and threaten to take you to Brazil or Cuba where slavery was still legal.15

In Brazoria County, some of Winston’s former slaves chose to stay. He offered them contracts and continued to rely on Black labor to work his land. In 1867, four men at Cedar Lake Plantation filed a claim with the Freedmen’s Bureau alleging that Winston withheld corn and other property rightfully due to them given the terms of the contract, in addition to threatening them with violence. The Freedmen’s Bureau determined that Winston needed to compensate the men.

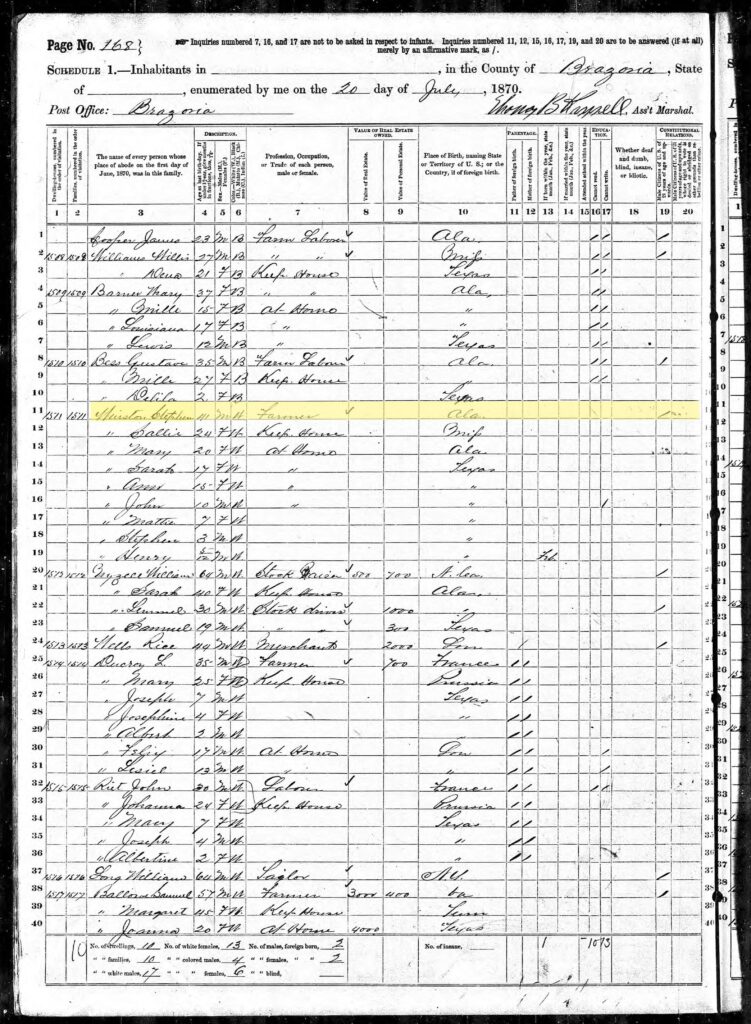

By 1870, Winston’s fortunes took a turn for the worse. He filed for bankruptcy and on May 30, 1871, he was officially declared bankrupt. Stephen P. Winston is last identified in the 1870 census, leaving his date of death unknown.

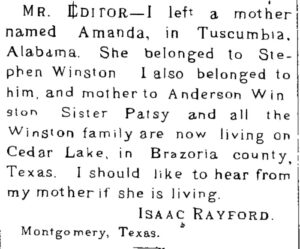

A decade after Winston filed bankruptcy, a man named Isaac Rayford placed an ad in the Southwestern Christian Advocate, a weekly newspaper in New Orleans, Louisiana, published by the Methodist Episcopal Church. Rayford was in search of his mother, Amanda. In his ad, Rayford shared that he left Amanda in Tuscumbia, Alabama, where they both belonged to Stephen Winston and Anderson Winston. He knew members of the Winston family were then living on Cedar Lake in Brazoria County, and wanted to know if his mother was still living.

Footnotes

1 Nancy Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms: Race, Rights, and the Politics of Household in the Delta, 1861-1875 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 28.

2 Caleb W. McDaniel, Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 169-170.